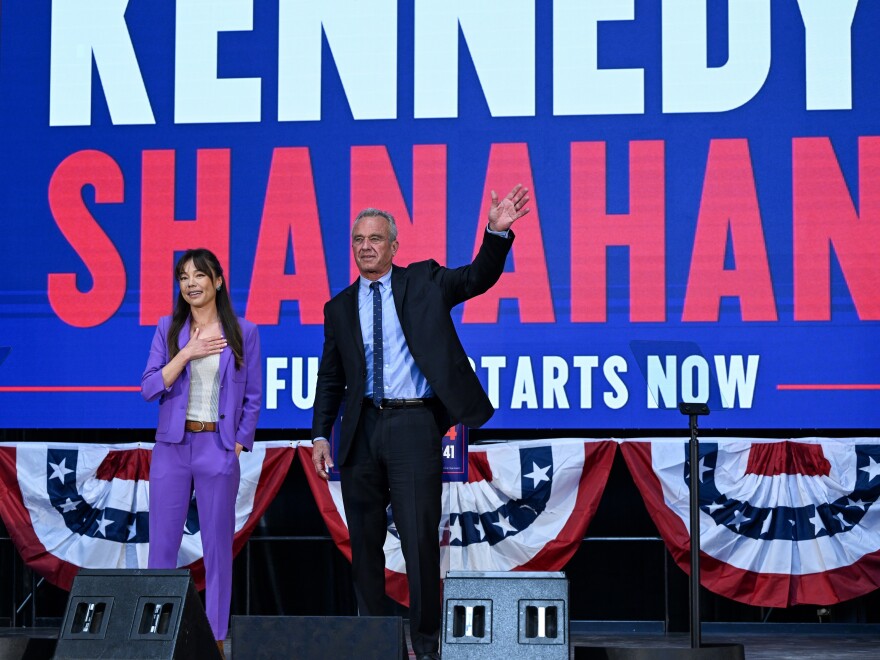

One of the most anticipated stories in politics this week was the announcement of a running mate by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the independent candidate for president. Kennedy introduced Nicole Shanahan as the woman he would make his vice president. Shanahan, 38, is an attorney and high-tech Silicon Valley businesswoman.

Shanahan made an appealing debut as a speaker, long on sincerity and concern for issues of the environment and health. She expressed doubts about the overuse of vaccines, a rather mild version of Kennedy's own well-known antipathy to them. She said her running mate was "the only one anti-war candidate today" in the 2024 field.

Some other figures Kennedy had recently mentioned publicly as prospects – such as Aaron Rodgers and Jesse Ventura – might have added a household name and perhaps a note of notoriety. But Rodgers, a former Most Valuable Player in the NFL, and Jesse Ventura, a former pro wrestler who served a term as governor of Minnesota, both said the job had never been officially offered to them. A case could be made that Kennedy had mentioned these men simply to gain attention for the campaign.

The person Kennedy had chosen instead seemed to add little by way of stature or visibility for his bid. So most of the immediate comment focused on what she presumably can offer, which is money. Her former husband, Sergey Brin, is a co-founder of Google whose fortune has been estimated at more than $100 billion. The settlement she received when the couple divorced has not been disclosed but is presumably substantial.

And she will be permitted to spend as much of it on the Kennedy-Shanahan ticket as she wishes, because the Supreme Court has since 1976 treated personal spending for one's own candidacy to be protected as "free speech" under the First Amendment.

Shanahan had previously been in the news for financing a $4 million ad buy for Kennedy during this year's Super Bowl broadcast. All presidential candidates need money for travel, staff, and above all, for advertising. Kennedy still needs money to fuel his ballot access campaign, which so far has him on the ballot only in Utah.

Still, until Shanahan can prove herself an asset in other ways, Kennedy will seem to have missed an opportunity to capture the imagination of the nation – or at least a meaningful segment of it.

Most independent or third-party candidates for president wind up being minor — if even measurable — influences on the November results. But Kennedy, 70, is still a scion of the most famous political family in America and has polled as high as 13% of the November vote in a recent Quinnipiac Poll.

That does not mean he could win the White House, or carry a single state. The last independent or third-party candidate to win a state was segregationist Gov. George Wallace of Alabama, who won five in the Deep South in 1968. Another segregationist, Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, won four states in 1948.

But Kennedy's current share of the vote means he could affect the outcome in a few swing states and thereby alter the outcome in the Electoral College. Anyone who remembers the Florida recount of 2000 knows that the votes cast for Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in that state might easily have swung the state for Democratic nominee Al Gore.

And beyond all that, this is 2024, and nothing about this cycle is normal. We have the two oldest nominees in presidential history winning their nominations historically early while more than 60% of all voters say they don't want these two as their choices in November. In theory, at least, Kennedy should be able to exploit these unusual circumstances.

So some will say Kennedy's opening demanded he do more to enhance his chances with his one choice for vice president.

The nature of the job

All vice presidents play second fiddle to the top of the ticket, as that's the nature of the job. Article Two of the Constitution included the office mainly to ensure a smooth and immediate transition in the event of a president's death, forestalling any uncertainty over succession. Yet the job has always been cursed with a kind of ambivalent status. In the major parties, it has long been a ritual for presidential candidates to forswear any interest in being No. 2.

That ambivalence has to be even greater when discussing running mates for third-party or independent candidates. After all, no independent candidate or third-party candidate has ever won the presidency, which has remained the province of the two major parties since the 1790s – even as those two parties have evolved, changing their names and geographical bases.

Given that record, running third-party or independent is more a quest than a reasoned proposition. So being the running mate carries a kind of double dose of humility. Such a candidate must always play Sancho Panza to someone else's Don Quixote, riding the burrow beside the questing knight.

There have been a few who had standing of their own, at least prior to accepting the running mate role. Prominent among them was Adm. James Stockdale, who was recruited by independent candidate Ross Perot in 1992 when Perot was leading both the incumbent President George H.W. Bush and Democratic challenger Bill Clinton in the polls.

Stockdale had been a naval aviator in the Vietnam War, taken prisoner and held for years in North Vietnam. He had a sterling reputation as a military leader and scholar, but he was not a practiced politician or media performer. In his debate against the Democratic and Republican vice presidential nominees, Al Gore and Dan Quayle, respectively, Stockdale's amiable attempt at self-deprecating humor went awry. His introductory line "Who am I? What am I doing here?" came across as genuine confusion and was widely parodied. Unfair as it was, one only gets one chance at making a first impression.

In 1968, Wallace had chosen for his vice president Gen. Curtis LeMay, a former chief of staff for the U.S. Air Force and a controversial architect of bombing campaigns in World War II. In 1948, Thurmond of South Carolina, ran with Mississippi Gov. Fielding Wright as his No. 2.

Making a mark of their own

At least a few independent or third-party running mates have made a mark for themselves after this moment of national exposure. Perhaps the most formidable of them was Hiram Johnson, the young reformist governor of California who became Teddy Roosevelt's political wingman in 1912.

Roosevelt, who had been president from 1901 through 1908, quickly soured on the man he had chosen as his successor, William Howard Taft. But when Roosevelt challenged Taft for the next Republican nomination, he fell far short. So the indomitable Roosevelt proceeded to run as the nominee of the Progressive Party, tapping Johnson to join him on what would be called the "Bull Moose ticket."

That ticket won 27% of the vote in the fall in a four-way race but carried only six states. It was enough to split the vote of the dominant GOP and hand the presidency to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

And it was one state more than James B. Weaver of the populist People's Party had won as the third-party challenger to President Benjamin Harrison and former President Grover Cleveland in 1892. Weaver's running mate, James G. Field, was a former Confederate Army officer and attorney general of Virginia.

Hiram Johnson was reelected governor in 1914, moved to the Senate as a progressive Republican two years later and served there until his death in 1945. He was known as an ally of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal and as an isolationist who opposed U.S. entry into the world wars, the League of Nations and the formation of the United Nations.

Another progressive hero with deep doubts about European wars was Robert M. La Follette Sr., known as "Fighting Bob" in his home state of Wisconsin. La Follette was the Progressive Party nominee for president in 1924 and carried his home state. His nominating convention adjourned without choosing a running mate for him. He later offered the job to Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who turned him down, and then to Montana Sen. Burton K. Wheeler, who accepted.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDA3NTgyODY4MDEzMDcxMjU4NjBlODYwNg001))