TRABZON, Turkey — They had reached the end of the road.

Sitting on a park bench in this small Turkish city on the Black Sea, Sayyid Ali Hussaini held his 9-year-old daughter as she slept. His wife Mahbube huddled next to him as the hours ticked past into the night. He had given all he had to the smugglers who shepherded him and his family out of Afghanistan and across the mountains in a grueling, monthlong journey through Iran to reach Turkey. Now, they weren't sure where they would sleep.

"When it's a matter of life or death for your family, everything changes," Hussaini says.

He walked a few steps away to have a smoke, and a stranger approached his wife and daughter with an unexpected question: "Are you new?"

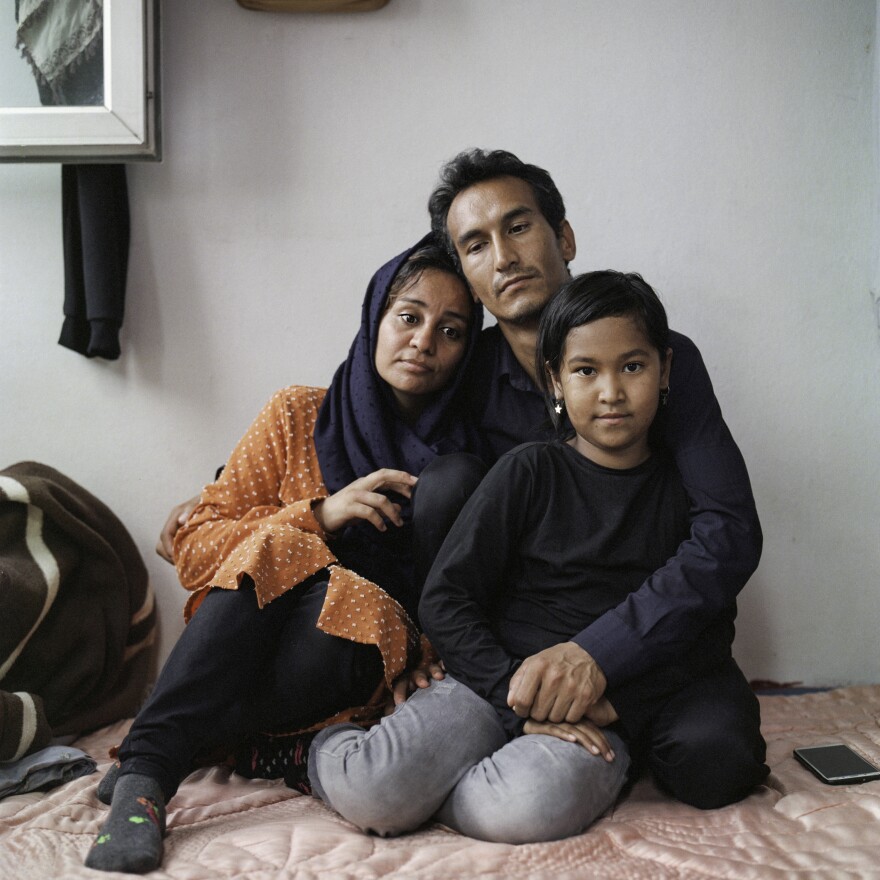

As it happened, the man was also an Afghan and lives in Trabzon. He took the little family in, letting them stay in a spare room in a shared apartment. That's where they spent about a week, keeping an eye on the news back home while they navigated the bureaucracy of becoming refugees in Turkey.

"I have a responsibility to my wife and daughter," Hussaini says. "I'll do everything I can to find a safe place for them, to make them happy."

Last month, the United States airlifted more than 122,000 people from Kabul as the Taliban took control of Afghanistan. Thousands more fled on foot, across the borders of Pakistan and Iran. Smaller numbers of Afghans have ventured into Turkey in hopes of reaching Europe. In response, Turkish authorities began extending a wall and beefed up patrols along the country's land border with Iran, a common route for asylum-seekers. More than 40,000 Afghans have been prevented from entering the country so far this year, officials say.

Turkey's leader has called on the West to shoulder the responsibility of housing refugees from America's longest war. Turkey already hosts 3.6 million refugees from Syria and 300,000 from Afghanistan, according to official figures.

"Turkey has no duty, responsibility or obligation to be Europe's refugee warehouse," Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said in a televised address last month.

The Taliban targeted his family

When Hussaini was about 8 years old, the Taliban came for his father.

One morning, they stormed the family's home in the quiet village of Chemtal, in northern Afghanistan against the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains.

"They beat me with the end of a gun," recalls Hussaini, now 31. "I still have the mark on my forehead. I don't know what our crime was."

Hussaini's family found themselves in the Taliban's crosshairs for two reasons. First, his father had previously served the Afghan army. Secondly, his family identifies as Hazara, an ethnic minority group that is deemed heretical and targeted by the Taliban for practicing Shia Islam. (He identifies both with the Hazaras and the Sayyid, a group that claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad and his relatives.)

To live in Chemtal after 1998 was to live in fear. Hussaini has memories of massacres targeting Hazaras and other minorities, as the Taliban jockeyed for power with local forces. When the U.S. invaded in 2001, the violence continued in the form of bombs and nighttime raids — for another 20 years.

"Both sides kill people in the name of Islam," Hussaini says. "I don't want the same life for my daughter, or my grandchildren."

Hussaini had built a comfortable life for himself as an electrician in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-e-Sharif. But even when the Taliban weren't in power, they made their presence known. Like the time he and his family were listening to Mahasti, a classic Persian pop star, in his father's garden. He remembers the song — "Meykhoone" — a sad tune about lost love in a world that now feels unreal.

"The Taliban came, and they beat me, because we were listening to music. That's when I decided Afghanistan was no place to live," he says.

This summer, as the Taliban gained momentum in an offensive that began in the east, Hussaini decided to hire smugglers to take him, Mahbube and Elisa across the border into Iran. He knew the Afghan National Army, no longer bolstered by U.S. firepower and intelligence, would likely fall to the Taliban. He wanted his family out before the country returned to the group that still haunted his childhood memories.

"They're the same Taliban," Hussaini says. "In the news you can see them saying, 'We're changed, we are a new Taliban,' but I don't trust them. The Taliban is the same."

Their escape begins

In July of this year, the Hussainis squeezed together into a smuggler's car on the road from the city of Herat. They were stopped at a checkpoint guarded by Taliban fighters, who ordered Hussaini to get out of the vehicle, and asked if he was Hazara. When he said he was, they beat him profusely.

"Just for being Hazara, just for being Shia," he says. "Even for one hour, if you go to Afghanistan, you will understand. Still, I have nightmares."

Hussaini still walks with a limp, clutching his side from the pain that shoots into his lungs if he lifts anything over 40 pounds. Near the Iranian border, the smugglers gave him a dose of the powerful opioid Tramadol. They packed themselves back into the car and pressed on.

As city after city fell to the Taliban, the smugglers sent the Hussainis on a circuitous trail through Iran. They rode out in the open, in buses when they could. Other times they rode in trucks, staying as silent as possible, concealed in compartments underneath goods. Slowly, they made their way from Herat to the Iranian pilgrimage site of Mashhad, to Tehran.

At last, they drew close to the border that snakes through the mountains between Iran and Turkey. They got out of the car, and were told to walk.

Turkey builds a border wall

Turkish officials knew that refugees were likely to come in large numbers, following the fall of Kabul. The government hastened to build a 183-mile-long wall along the eastern border with Iran. The long line of 10-foot-high concrete slabs comes with a bevy of increased patrols.

For decades, Afghans have passed through Turkey on their way to Europe. Others arrive on student or work visas and live in Turkey permanently.

But anti-immigration sentiment has mounted in Turkey, which escalated to a riot targeting a Syrian neighborhood in the country's capital last month.

In Trabzon, the refugee community is smaller, and tensions are lower. But the local newspaper runs breathless headlines about refugees who are caught trying to cross the border, and accusations about Afghans "invading" local neighborhoods amid rising crime rates.

At a teahouse, where retirees and old friends play backgammon and a Turkish tile game called Okey, Sayed Yaranli says he isn't necessarily opposed to new arrivals in Trabzon. But he wonders, if the roles were reversed, would Afghans welcome Turks into their country? And what about the coronavirus — could migrants carry it over the border?

His friend, sitting at a table, pops up with another question. "Why don't they stay and fight?" he asks.

Hot food and a bus to Iran

After decades of war that stripped away his loved ones, his livelihood and his hopes, staying was no option for Hussaini. The journey to Turkey became his fight.

In a series of videos that he texted to the smugglers on WhatsApp, Hussaini berated the smugglers for the conditions as they passed through Iran. The smugglers charged inflated prices for cellphone SIM cards and bottled water. His daughter's arms were covered in insect bites, after sleeping on the dirt floors of safe houses that felt like they were crumbling around them.

"You human traffickers, look at this," he said, unable to keep the anger out of his voice as he panned the camera of his phone around a small room with a partially caved-in roof.

Eventually, they reached a barbed wire-topped fence marking the border between Iran and Turkey. They shimmied underneath, crossing a ditch littered with clothes and food left by other migrants. But it wasn't long before they were spotted and arrested by Turkish patrols, and deported back to Iran.

"We were treated with respect. We hadn't eaten anything that day, we were so hungry. The Turkish police fed us, and then they sent us back to Iran," he said.

They called the smugglers, who sent them to stay with a family of shepherds, living in tents. The next day, they walked to the border a second time. Again, the Hussainis were arrested and deported.

On their third attempt, they were told to hike through a valley to reach another section of the border near a customs station, where a cement wall separates the countries. This time, they climbed over the wall, and made it to a safe house farther inside Turkish territory. But a drunken fight between the smuggler and the owner of the home turned violent.

"The Turkish smuggler drew a big knife and tried to attack the owner of the safe house. The house was full of families and little children, and I put myself between them — he cut my arm," Hussaini says.

The homeowner escaped and called the police. When the authorities arrived, they separated the migrants into two groups — families and men traveling alone. They deported the unaccompanied men. Families were free to go.

Hussaini and his wife and daughter made their way to Trabzon. A friend told Hussaini that there were jobs there. He had spent his life savings to pay the smugglers — the equivalent of about $4,300 in cash.

Now, he counts out the change left in his wallet — it's about 48 Turkish liras, equal to less than $6. That's all he has left.

Afghans help each other find a new life

At least 35 families from Afghanistan have arrived in Trabzon over the past three months, according to the records of the Afghanistan Hazaras Culture and Solidarity Organization, an aid group based in Turkey.

For many Afghans, one of the first stops when they arrive in Trabzon is a dry goods shop owned by Ahmad Javaheri, who is from the western Afghan city of Herat. There are candies imported from Iran and Afghanistan, different types of lentils, and brands of rice that are familiar to Afghan shoppers. Packets of saffron and imported teas line the walls. Small comforts of home.

"When a newcomer comes to Trabzon, we don't let them stay outside. We take them in until they find a place to rent," Javaheri says. "I try to find jobs for them, and recommend them to our Turkish friends."

Javaheri once owned a currency exchange office in Herat and brought his family to Turkey four years ago. Near the cash register, he keeps a small can collecting donations for the new arrivals.

A lot of these families had work, furnished homes and comfortable lives back in Afghanistan, he says. In Turkey, they start from zero — often working factory jobs that carry a high risk of injury and sending as much money as possible to their relatives back home.

"They risk their lives for 100 Turkish lira [$11.85]," he sighs, referring to a day's wage. "But if your family is in danger, and you can't make money in Afghanistan, what would you do?"

Mohammad Bashir Salar, who is from Bamiyan, Afghanistan, and runs a small Afghan restaurant in Trabzon with his wife, says he's waited three years to be resettled in the West. Every year the United Nations' refugee agency can resettle a limited number of people, and many applications get rejected.

He says he wishes he could tell people in Afghanistan to stay put if they can make it work.

"I'd tell them that if the Taliban say you're safe and really, you're safe — stay there. We're here [in Turkey] as immigrants, and we're not happy here," he says.

Seeing the future in a hopeful daughter

A pile of donated blankets and a portable cookstove sit in the corner of the tiny room in an apartment Hussaini and his family share with other Afghans, overlooking a busy road. Ali has found work mending equipment for fisheries on the coast, but he hasn't been able to get medical care for the pain in his side.

On a sunny afternoon, 9-year-old Elisa pulls out a notebook she uses in the quiet moments, to teach Mahbube, 25, to read and write.

It's full of detailed drawings in colored pencil. In one, she explains, a Taliban fighter has a gun in one hand and in the other, a bomb. But in another picture, the little girl and her father are holding hands and smiling, standing together on a grassy hill.

"The Taliban are crushing the people of Afghanistan like flowers," she reads out loud from a description of the first drawing.

In the second, she reads, "They can't bring down my country's flag. They can't darken my sun."

Elisa is hopeful. And as her father watches, he says that her hope is why they are here.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.