On a recent Saturday afternoon at his West Baltimore row house, Harrelle Felipa fields a steady stream of interruptions as he breads a large plate of fish and chicken for dinner.

His 4-year-old son wants to recite his letters. The 3-year-old brings him a toy that's broken. The tweens play Minecraft on the Xbox while Felipa's teen daughter checks her email. Felipa says he loves it.

"This is what my life consists of," he says. "I arrange my life around these guys."

It's not the typical image of a "deadbeat dad."

Yet 47-year-old Felipa owes $20,000 in unpaid child support. Over the years, he has lost his driver's license for that (for two months), and spent time in jail for missing a court appointment (for two weeks).

He is part of a shift: Despite a two-decade crackdown on delinquent dads — an enforcement push that officials say has largely worked — the U.S. has more than $113 billion in child support debt. The Obama administration, and others who support changes to child support enforcement, say this isn't because men who have the means won't pay.

"That problem has been solved," says Vicki Turetsky, the head of the federal Office of Child Support Enforcement. That's thanks to welfare reform in 1996, which included tougher rules that tracked down men with money.

The problem today, Turetsky says, is the many men without money. They don't earn enough, and they're accruing mountains of debt in back child support.

Caught Between Parenting And Mounting Debt

Take Felipa in Baltimore, for instance. He had his first child young, at 14. His own father wasn't around, and he says being a dad makes him feel complete.

Like so many families today, his is complicated. He has five young sons with a woman he calls his "ex-fiancee." The boys have lived with him much of the time while their mother has worked as a restaurant manager.

Felipa's child support debt is for two teens with his ex-wife. The son lives with her, and Felipa has full custody of their 15-year-old daughter. Yes, you read that right: He owes child support for someone who lives with him full time.

It's not clear why; he's been asking the court to change it.

Maryland enforcement officials can't comment on specific cases. But they say custody and child support are often dealt with separately, the rules vary by state and are confusing, and changing a child support order can take many months. Some parents also have no right to a lawyer. Felipa says tensions over his child support situation helped lead to the breakup with his fiancee.

Felipa admits it's tough getting by with so many kids. He's paid child support sporadically, most recently when he was employed as a truck driver.

"I was making $1,300 every two weeks and they were taking five [hundred]-something out every two weeks," he says. "After the taxes and all that, can you imagine what [that] left me?"

Current federal guidelines allow states to garnish up to 65 percent of a parent's pretax income for child support. One study found that among parents with reported annual incomes of $10,000 or less, the median child support order represents 83 percent of their income.

Felipa says his child support order didn't leave him enough for child care. His hours were tough, leaving at 4 or 5 in the morning, sometimes not getting back until 8 or 9 at night. He hated leaving the kids with a sitter.

"Sometimes you get that gut feeling, and when they cry, I just couldn't do it," he says. "I felt something wasn't right."

So, in a move not likely to get much sympathy in family court, Felipa quit working. For two years he has relied on food stamps and other aid while his child support debt has ballooned.

'Income That Doesn't Exist'

"When people have orders that they can't comply with, it doesn't motivate them to work and pay. It does the opposite," says Turetsky of the Office of Child Support Enforcement.

She says too many men quit jobs, turn down promotions or go underground when courts set child support orders too high. One problem, she says, is that when there's no evidence of income, many jurisdictions "impute" it, often basing payments on a full-time minimum wage job.

"I'm going to call it magical thinking," Turetsky says. "You could call it the income we think you should have. But the bottom line is that it is income that does not exist."

The child support system was set up four decades ago, and Turetsky says it seems stuck there — as if a man with no college can still walk into a factory tomorrow and pull down middle-class wages. In fact, a large majority of child support debt is owed by men who make less than $10,000 a year.

"We're asking that [women and children] become dependent on men who are just as poor as they are," says Jacquelyn Boggess of the Center for Family Policy and Practice.

When parents face incarceration for nonpayment, it can burden entire families. Boggess has seen men's mothers, even their ex-girlfriends or wives, step in to pay to keep a father out of jail. And child support debt never goes away, even if you declare bankruptcy or when the children grow up.

"We found that there are 20- and 30-year-old children who are paying their father's child support debt, so their father can keep whatever small income they may have," she says.

Another quirk in the system is that many men rack up child support debt while in jail. After Antonio Martin's ex-girlfriend lost her company health insurance, she had to give the government Martin's name, as it was a requirement in order to get Medicaid coverage for their daughter. Martin was serving seven years for robbery when the child support order came.

It was "$183.50 twice a month," he says. "So in my mind I'm thinking, upon release I'll start paying this amount of money."

Enforcement officials say that happens a lot. Some parents don't realize they can file to defer payments. But many states consider incarceration "voluntary employment" and no excuse to suspend child support. Martin's debt added up, month after month.

"When I came home and I got the first letter," he recalls, "I was seeing it was $4,000 on there."

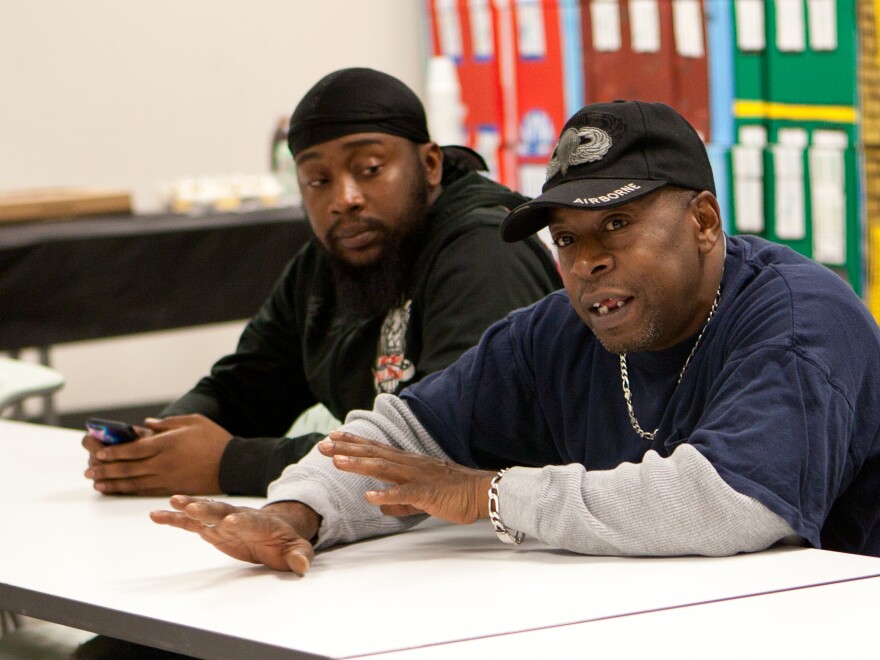

That was two years ago. With his criminal record, Martin has struggled to find work. His debt is now approaching $6,000. Martin recently completed a job training program at the Center for Urban Families in Baltimore, hoping to find any job he can to start paying down his debt. Eventually, he hopes to get certified for work in plumbing or carpentry.

Balancing Responsibility And Reality

Among the Obama administration's proposed changes to child support rules is a provision barring states from letting child support pile up in prison. There is wide support for that, even among conservatives.

"Everyone agrees, yes, we should be tough," says Ron Haskins of the Brookings Institution. "But if a father goes to jail for five years, should he owe $15,000 in child support when he comes out? You know that guy's never going to have $15,000 in his whole life."

More controversially, the administration wants to make sure child support orders are based on a parent's actual income.

"We can't be naive when we're dealing with parents who have walked away from providing for their children," says Robert Doar, of the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

Doar, who used to head child support enforcement in New York state, says there will always be some parents who go to great lengths to hide income. He does support suspending debt during incarceration and more job training programs — but he worries that the proposed changes would make it too easy to dismiss cases as "uncollectible."

"We're talking about poor, single parents, often moms," he says. "And the child support collections that they get, when they get it, represents 45 percent of their income."

Republicans on Capitol Hill have filed bills to block the proposed regulations. They worry they'll undermine the principle of personal responsibility, a hallmark of child support enforcement measures in the 1990s. They also say any regulatory changes should be made through Congress, not the administration.

Meanwhile, Harrelle Felipa continues to do the best he can. His youngest will head to school soon, and the boy's mom — Felipa's ex-fiancee. — recently lost her job. So Felipa is looking to work again. He's been volunteering at an elementary school and is talking with the principal about a paid position. This time, he hopes what's left in his paycheck after child support will be enough.

Copyright 2024 NPR