One hundred years ago today, Cleveland Indians batter Ray Chapman died after being struck by a ball thrown by Yankees pitcher Carl Mays. The fatal pitch set in motion a tragic series of events that would claim more than one victim.

Michael Sowell, author of “The Pitch That Killed” and Jeremy Feador, the Cleveland Indians’ Team Historian reflect on this singular baseball tragedy.

Why was Chapman hit?

Although much of the blame was put on Mays, the catcher at the fateful game claimed the pitch was a strike.

Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman, who was fatally hit by a pitch on August 16. 1920. [Library of Congress]

“The catcher claimed that Chapman's head, actually, was leaned over the plate and he was in the strike zone,” said Sowell. “Ray Chapman did not move at all. He made no effort to get out of the way of that pitch. So there's speculation, maybe he didn't see the ball. He lost the ball.”

According to Feador, the ball was a lot easier to lose back then: “In 1920, you're still using a baseball, a single baseball, most of the game. It would get kind of damaged and muddied.”

But Sowell has another theory: Chapman became momentarily mesmerized.

“One of Chapman's former teammates, a guy named Terry Turner, described when he was hit by a pitch in the head, and he recalled that the pitch was coming, and he knew it was going to hit him, but he became fascinated with the ball,” said Sowell.

“He likened it to a snake about to strike and bite you. You're looking at it and you can't move.”

Blame Went to Mays

“Both men became victims of that pitch,” said Sowell. “Ray Chapman lost his life. Carl Mays lost his reputation.”

Carl Mays, the Yankees pitcher who fatally struck Chapman. [Library of Congress]

Rather than implementing safety measures, much of the league blamed pitcher Carl Mays, who was widely disliked and had a reputation for hitting batters.

“The players around the American League wanted to have Carl Mays banned from baseball,” said Sowell.

An article from the Buffalo Courier on August 21, 1920 claimed that Mays suffered a nervous breakdown after killing Chapman.

“In fact, initially, he had to go down to the district attorney's office, because there was some thought he might be charged with manslaughter or some other kind of homicide. Of course, no legal charges were brought against him.”

Baseball helmets would not appear in Major League Baseball for decades.

“Some people think this, obviously, would lead to the batting helmets that players wear today,” said Sowell. “And yet it took about 30 more years before they started slowly coming into play.”

A Ghost Story

After Chapman died, the story became even more tragic. He left behind a pregnant wife, Kathleen Daly Chapman, who was devastated by the news.

Chapman's wife Kathleen Daly was the daughter of a wealthy Cleveland businessman. They were married less than a year before Chapman died. [The Plain Dealer, 1920]

“She later gave birth to a little girl. The girl's name was Rae Marie,” said Sowell. “But Kathleen never really overcame this.”

She remarried and moved to California, but Kathleen died in 1928 after drinking poison. After her death, Rae Marie was raised by the wealthy Daly family in Cleveland.

“One day she told her nurse, ‘I spoke to my mother last night, and she said I'll be joining her soon,’” said Sowell, recalling a story Kathleen’s brother shared with him. “A week later, the little girl got the measles. She died.”

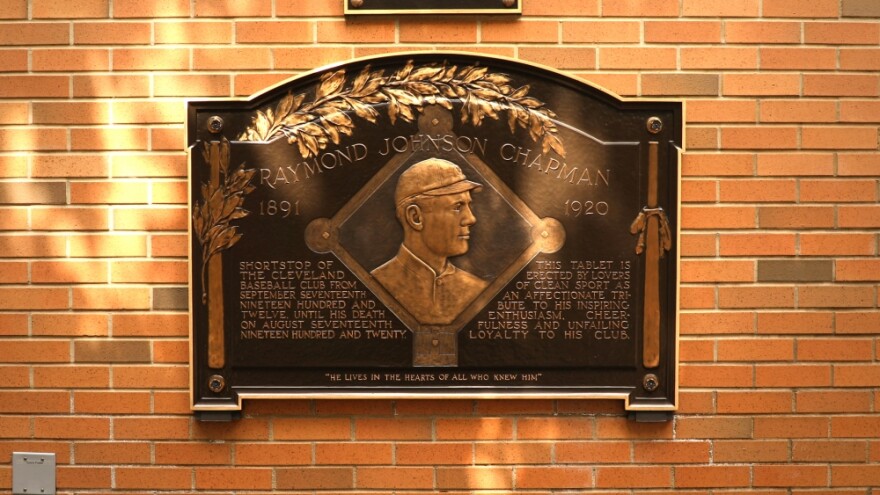

Ray’s Missing Plaque

Today, visitors to Progressive Field can pay their respects to Ray Chapman at his plaque, displayed in Heritage Park.

“One of the things that people wanted to do was create some sort of memorial to Ray,” said Feador. “The plaque came out shortly after the 1920 season.”

An article in the Plain Dealer on September 30, 1920 describes the plaque that would eventually be created in Chapman's honor.

It was originally displayed under lights at League Park, the Indians’ first home, but when the Indians moved to Municipal Stadium in the 40s, the plaque was misplaced.

“For the longest time, the plaque was just kind of hiding. And when it was found in 2007, it needed to be cleaned up,” said Feador.

According to Feador, the restoration of the plaque coincided with the opening of Heritage Park, which pays tribute to former Indians greats.

Raymond Chapman's plaque displayed in Heritage Park at Progressive Field in Cleveland. [Mary Fecteau/ideastream]

“People go to museums and you can't touch anything,” said Feador. “This sign is about a hundred years old and you can touch something that is a piece of history.”

![Ray's wife Kathleen Daly was the daughter of a wealthy Cleveland businessman. They were married less than a year before Chapman died. [The Plain Dealer, 1920]](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/9baa9dc/2147483647/strip/true/crop/583x1000+0+0/resize/880x1509!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Flegacy%2Fusers%2Fmfecteau%2F2020%2F08%2Fkathleen.jpg)