Statues honoring certain historic figures are coming down across the country as a nation reckons with its past. The Cleveland Restoration Society is looking to flip that script by installing a series of public markers to trace the Civil Rights struggle in Northeast Ohio. They’re conducting a survey to help determine likely sites.

The Cleveland Restoration Society was founded in 1972 to help preserve buildings and other places that make up the city’s historical heritage. But Executive Director Kathleen Crowther said for many years, not every voice was heard when it came to identifying all the pieces of that history.

Ten Ohio historical markers will be installed at Ciivil Rights history sites around Northeast Ohio. [David C. Barnett / ideastream]

"You know, Cleveland turned a corner some years ago, when it became a majority-minority community," she said. "And yet, we have not really found those places that properly reflect the history and heritage of what is the majority demographic for our city."

Crowther added that this project was not inspired by the current national discussion about race.

"We started this over a year ago and our work in African American history documentation is coming on ten years old now," she said. "It’s stunning to me, because we knew a year ago when we started that it has relevance today, but we’re in such a dynamic period, now, that we had no idea ... that we were walking into this."

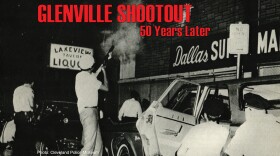

Glenville shootout, 1968 [Cleveland Memory Project]

The survey offers suggestions of sites to consider across the city. Crowther said some of them are “no-brainers,” like Cory United Methodist Church, a former Jewish meeting and recreation center that became a Black church after World War 2. During the 1960s, Cory hosted numerous appearances by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Malcolm X debuted the first iteration of his famous “Ballot or the Bullet” speech from the Cory pulpit in 1964.

Cory United Methodist Church [Cleveland State University Special Collections]

Cory's place in civil rights history is well-documented, but Crowther suspects there is much more to discover. She points to the story of the Sidaway footbridge, suspended above Cleveland’s industrial valley, linking the predominantly Black Kinsman Road neighborhood with the largely white enclave of Slavic Village.

"It was a way for workers to get from Kinsman to jobs in Slavic Village, children on Kinsman to get the school in Slavic Village,” Crowther said. “And so, as it became the subject of vandalism, it was illustrating the racial hatred that existed in Slavic Village to Kinsman.”

The abandoned Sidaway bridge [atlasobscura.com]

That perspective was first brought to the attention of project leaders by a local community member. Kathleen Crowther said such stories will be combined with the insights of historians and others to help add deeper meaning to this project, documenting Cleveland’s Civil Rights Trail.

![Issac Haggins sold homes to African Americans at a time when white realtors wouldn't. His office was bombed in 1969. [Cleveland Memory Project]](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/5a65b70/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1108x670+0+0/resize/880x532!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Flegacy%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F7%2F31%2FHaggins%20Realty.jpg)