No one knows what causes schizophrenia. It’s a devastating mental disorder that affects more than 3 million Americans.

And while most people with schizophrenia can be treated, many don’t respond to medications.

New research may find ways to help them.

In this week’s Exploradio, we examine how genetic research is providing clues to the unsolved mysteries of schizophrenia.

It all started during Brittany’s sophomore year in college.

She began to believe people were after her. “Men in suits specifically. They were faceless and there were many times I would see a faceless man in a suit and I thought they were following me,” she recalls.

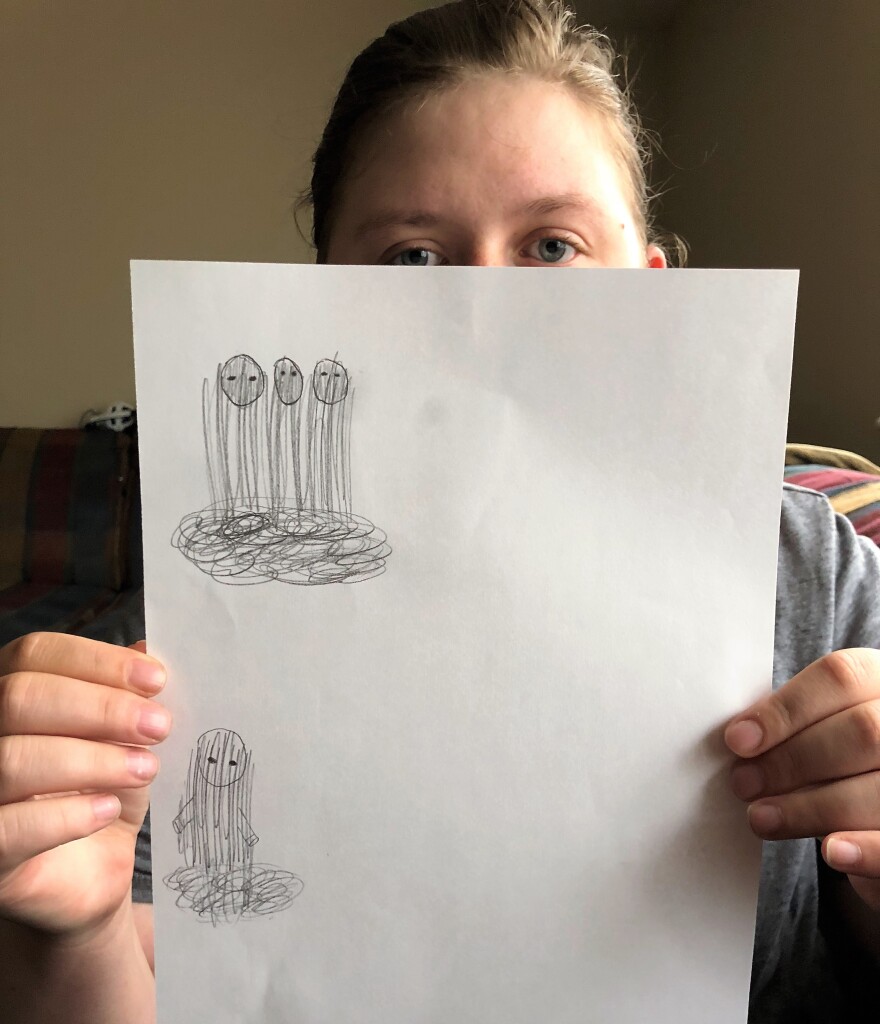

She show me a sketch of other pursuers, formless people enveloped in smoke. “But what you could see were their eyes," she says, "and they were always black and they were always piercing…”

Months went by as, still in school, life for Brittany – who asked that I don’t use her last name - descended into a nightmare.

She believed the shadowy figures wanted to kidnap her. "I thought people wanted to take me away," she says.

Eventually Brittany sought help, and now with medication, she rarely sees the men in suits.

"I can thankfully say that I’m doing much better.”

Brittany is typical in that, like most people with schizophrenia, it hit her in her late teens.

A developmental disease.

Dr. Erik Messamore runs the Best Practices in Schizophrenia Treatment, or BeST Center, at Northeast Ohio Medical University.

He says the brain undergoes a lot of changes during the transition to adulthood.

Hormones alter brain chemistry, we experience new types of stress, and our brain undergoes a period of intense re-wiring. “A process called pruning,” says Messamore.

New brain circuits form and others recede, and inherent schizophrenic pathways can be revealed.

“We call that the neurodevelopmental hypothesis,” he says.

Still, Messamore acknowledges that our explanations for schizophrenia remain vague, its mysteries only deepened by bizarre clues, beginning with our skin.

Schizophrenia and inflammation

Messamore is among a handful of researchers who have looked in the unique response people with schizophrenia have to what's called the niacin flush.

Say you take too much vitamin B3, or niacin, you get a rash. It’s ok - it’ll go away.

This happens to nearly everybody - except people with schizophrenia. They rarely get a rash. And no one knows why.

Messamore has a theory. He says it has something to do with the way our body signals inflammation, both in the skin and in the brain, through chemicals called prostaglandins. They play a role in the release of certain neurotransmitters, including dopamine, that may produce the hallucinations associated with schizophrenia. But it's a line of research that few people have pursued.

And this leads to another mystery. People with schizophrenia don’t get arthritis.

Gene expression puzzle

Dr. Vishwajit Nimgaonkar heads a team of researchers at the University of Pittsburgh that’s looking at the genetic underpinnings of schizophrenia.

He’s found that many of the same genes that cause rheumatoid arthritis are involved in schizophrenia, but in a different way. Instead of the joints, he says, they’re affecting the brain.

“What we are arguing is that there might be immune abnormalities in the brains of people with schizophrenia.”

Nimgaonkar's work points to more than a hundred domains, and around a thousand individual genes associated with schizophrenia, and he says their intricate interplay produces the surprising protection against arthritis.

“It’s like a jigsaw puzzle if you like,” says Nimgaonkar.

His colleague at the University of Pittsburgh, Madhavi Ganapathiraju is screening FDA approved drugs that might be re-used to treat the disease. And she says some of the most promising are similar to common anti-inflammatory medications.

“Imagine something as simple as ibuprofen," says Ganapathiraju, "treating schizophrenia.”

She’s excited by the insights advanced genetic analyses are providing - “We are at the cusp of major breakthroughs…”

Meanwhile, a group at MIT has identified a gene that mediates the neural pruning that NEOMED’s Erik Messamore mentioned.

Genes and other risk factors

Messamore says all of the research points to one conclusion.

“Schizophrenia is not a single disease with a single cause,” he says.

While mostly genetic, environmental risk factors can trigger the onset of symptoms, says Messamore. Stress, certain infections, and a plant that’s gaining popularity as a medicine: marijuana.

Messamore believes society is drastically underestimating the risks young people face from cannabis use.

“During adolescence the brain is rewiring itself - it’s doing massive amounts of reorganization," he says, "and this potently brain active chemical can interact in who knows how many ways.”

Medicine's final frontier

Marijuana was not a factor in Brittany’s schizophrenia. She doesn’t know what caused it.

She’s working with Dr. Messamore and his team at NEOMED to help others like her adapt to life with the disease.

“My goal is to help other people recover and help them realize that recovery is possible,” she says.

Psychiatry is medicine’s final frontier, according to Pittsburgh's Vishwajit Nimgaonkar.

But new research tools and treatment practices are slowly pulling back the curtain on schizophrenia and adding new ways to heal its dramatic break with reality.