It’s been called the miracle material - strong, lightweight, flexible, bendable, super-conducting, transparent - graphene is also among the most hyped materials known.

In this week’s Exploradio, WKSU’s Jeff St.Clair looks at local research in graphene, and tries to separate the promise from the fluff surrounding the world’s newest wonder material.

It’s probably the only experimental substance with its own PR firm - a billion-dollar European effort called the Graphene Flagship that produced this video starring G, the graphene superhero.

“G is the world’s strongest material -- harder than diamond and about 300 times stronger than steel…”

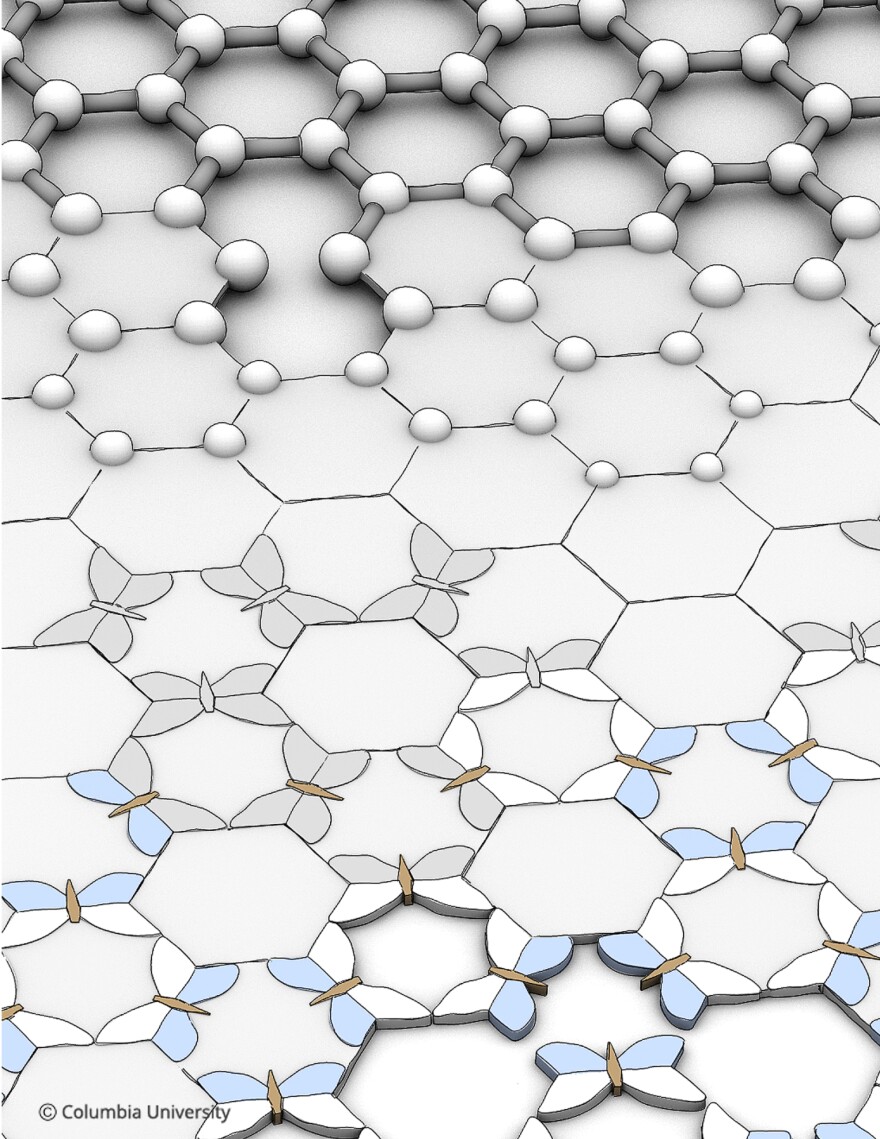

Graphene is unique. It’s the world’s first two-dimensional material, made of a single layer of carbon atoms, arranged in a sheet one atom thick.

And, although its structure was predicted decades ago, most scientists believed it couldn’t exist.

That is, until 2004 when researchers at the University of Manchester found graphene, in of all places, ordinary pencil lead.

The discovery earned them the 2010 Nobel Prize.

“I think it is an amazing material,” says James Tour at Rice University in Texas, one of the world leaders in graphene research.

He says graphene’s atomic structure provides its amazing properties.

“One of the strongest bonds in the universe is the carbon-carbon bond," says Tour, "and that’s what graphene is.”

Tour has used graphene to strengthen plastics, to make fuel cells; he’s used it in aerospace and biomedical applications.

“It can be used quite broadly,” says Tour, perhaps limited only by our imaginations.

Graphene batteries in Akron

Yu Zhu did his post-doc work with James Tour. He now runs his own lab at the University of Akron.

He’s using graphene to make the next generation of lithium ion batteries.

“Because graphene is highly conductive," says Zhu, "the power density is very high and you can have something that charges and discharges much faster.”

He says graphene batteries can last twice as long as current rechargeable batteries.

An Ohio company, Angstron Materials in Dayton is the world’s largest supplier of battery grade graphene. But Zhu makes his own using graphite as the raw material. It’s one of two processes he uses to make graphene.

The second is a high temperature vapor deposition method that produces small amounts of the high-grade graphene that he’s testing for the holy grail of graphene applications -- cell-phone touch screens.

But when I ask to see some, he just smiles and reminds me that crystalline graphene is just a one layer of carbon atoms, "so you don’t really see it with your eye.”

After all, it’s transparent, and conductive, the two properties that make graphene so desirable for electronic displays.

Back in his office, Zhu shows me samples of the displays he’s working on. One uses glass as the substrate, the other one is a polymer-based substrate that is flexible and nearly unbreakable.

But Zhu says we're still about a decade away from seeing a cell phone for sale with a flexible display that will never break.

Beyond the hype

Marko Spasenovic, a graphene researcher in Belgrade, Serbia, and a market watcher through his website Graphene Tracker, agrees.

Electronic displays are applications that require very high quality graphene at a low price, says Spasenovich and, "you’re competing with established technologies.”

Spasenovic says techniques currently do not exist to make large amounts of high grade graphene cheaply, but could be coming in the next decade.

That’s why he cautions people to avoid hucksters still riding the wave of hype surrounding the wonder material.

“I wouldn’t advise anybody to invest in any kind of graphene stock,” says Spasenovic.

But with hundreds of labs working on it, Spasenovic says a breakthrough in graphene production could be coming, just not on anyone’s news cycle.

“Technology is very hard to predict and scientific research is, I think, impossible to predict," says Spasenovic, "which makes it exciting.”

With its promise and its hype, graphene, to paraphrase Bill Gates, is one of those technologies where we highly overestimate it’s short-term impact, and deeply underestimate the changes it will bring years from now.