Ohioans say the economy and jobs are the most important issue in this election.

Talk long enough, though, and the word “trade” comes up.

There is a sense that cheap imports are behind the demise of Ohio’s manufacturing work force. Income numbers, at first glance, support the claim. Ohio, consistently among the top manufacturing states, had the second-largest drop in household median income in the country in the last 15 years.

The Buckeye State has a large number of hurting, if not angry people.

According to polling by the Bliss Institute of Applied Politics for the Your Vote Ohio project, Donald Trump’s anti-trade talk has resonated with Ohioans whose age, gender and education level define a once proud workforce in the state’s teaming factories. The billionaire’s campaign playbook includes a chapter critical of Hillary Clinton’s global trade policies, which some perceive as both the cause of the state’s decline and a chief threat to its revival.

“You go to New England, Ohio, Pennsylvania, you go anywhere you want, Secretary Clinton, and you will see devastation where manufacturing is down 30, 40, sometimes 50 percent. NAFTA is the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere but certainly ever signed in this country,” Trump said at the first presidential debate, blaming Clinton’s support of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement while First Lady more than 20 years ago.

Trump is correct in that major urban areas in Ohio have lost more than 30 percent of their goods-producing jobs since 2000, among them the Akron, Canton, Cleveland, Warren, Dayton, Cincinnati and Columbus areas.

But there’s a risk of over-simplification. The Midwestern manufacturing juggernaut that transformed the world was old and wheezing by the 1970s, a decade before the first American free-trade deal was struck.

Bad joke

There’s a political joke making the rounds online and, from Trump’s lips, at political rallies:

“Not long ago GM was building cars in Flint, Michigan, and you couldn’t drink the water in Mexico. After seven-plus years of Obama’s administration, GM now builds cars in Mexico and you can’t drink the water in Flint, Michigan.

“Hope and change delivered!”

Indeed, the value of U.S. imports from Mexico is about twice the exports to Mexico.

But the short joke misrepresents the complexity of trade. NAFTA, for example, liberalized trade by eliminating duties on many products shipped to or from Canada and Mexico. It initially was proposed by Ronald Reagan, negotiated by George H.W. Bush in 1992 and approved by Congress in 1993.

But Ohio’s core manufacturing jobs — rubber, automotive, steel — began to crack years earlier. One need look no farther than downtown Akron, Cleveland or Youngstown in the mid-1980s to see the vacant factories.

General Motors is a case in point.

GM’s first Mexican plant opened in 1981 when Reagan was president — not in the last seven years. Two more opened in 1994-95 during the Bill Clinton administration and three during under George W. Bush.

Contrary to the joke, a turnabout began during the administration of Barack Obama. GM has spent $2.5 billion alone in Flint since 2009 to modernize production and announced this year that some production will return from Mexico.

But don’t expect a resurgence in high-paying jobs.

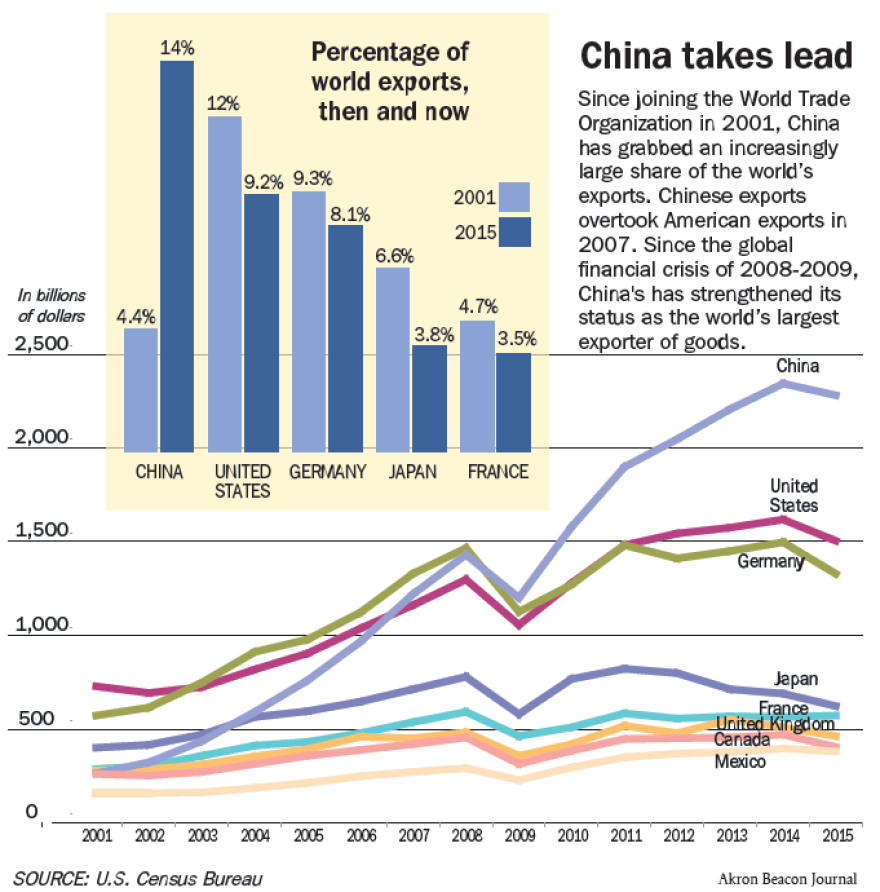

China, after entering the World Trade Organization in 2001, has overtaken America to become the world’s biggest exporter of goods. With cheap labor and newly constructed facilities, China has reset the stage for more efficient and cost-effective manufacturing, making it difficult for American employers to compete.

Researchers led by MIT economist David Autor reckon that 560,000 American jobs disappeared due to the rise of Chinese exports between 1999 and 2011.

But like most economists, the group recognizes that automation and technological advances in manufacturing have erased a larger portion of the 5.8 million factory jobs lost in America in that time period.

As Ned Hill, professor of public affairs and city and regional planning at Ohio State’s John Glenn College of Public Affairs, told the Toledo Blade in its examination of NAFTA: “Plants in Toledo were old and outdated.”

“The companies weren’t inventing new products and they were the highest-cost plants to operate. When demand for the products quieted down, the highest-cost, lowest-efficient plants were shut down.”

Whether it was from plant improvements or, as Hill suggests, a shutdown of old, inefficient plants, the country’s ability to manufacture goods with fewer workers made its biggest jump in three decades just between 2000 and 2007, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Good business?

As Ohioans struggle to explain losses in manufacturing jobs, issues of trade with Mexico and China have bubbled to the surface in the 2016 presidential election.

By focusing on Clinton’s support of free trade, Trump has won support in Ohio — despite his own use of overseas manufacturing for Trump-brand shirts, suits, furniture, lighting fixtures, eyeglasses, vodka, hotel soap and shampoo and more, according to Washington Post research. Trump has attacked Clinton for her prior support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a deal that aims to boost trade with countries that hang in the balance between the U.S. and China.

Trump blames “soft and weak and frankly stupid and incompetent” politicians from both parties for poorly negotiating trade deals. In the primary, Democrat Bernie Sanders blamed corporate greed for corporations that put profits before patriotism by off-shoring labor, skirting taxes and not sharing earnings with workers.

At the checkout

American consumers recognize that the shoes, shirts and toasters they buy are likely made in Vietnam, China or other places. But when attacking trade, protectionists like Trump and Sanders neglect to add up consumer savings at the checkout counter.

At one time, Ohio median household income was among the highest in country. However, since 2000, Ohio median household income is down 16 percent — worse than the national decline of 10 percent — and now $5,000 below the U.S. rate.

A solution to rebalancing trade deficits, imposing tariffs on goods that compete with American jobs could in fact backfire, squeezing the pocketbooks of everyday Americans faster than creating more jobs.

Pablo Fajgelbaum of the University of California and Amit Khandelwal of Columbia University have studied the benefits of cheaper imports on consumers who buy them. By tightly closing borders, the wealthiest wage earners would lose 28 percent of their purchasing power, the economists reckon, while the poorest would lose 63 percent — illustrating again the complexity of the many trade-offs of free trade.

“There are definitely two sides to this story,” said Alan Tonelson, an economist who has written about Trump’s proposal to rewrite NAFTA, the downfall of manufacturing and how trade impacts domestic production. Tonelson, complicating the argument that trade is either good or bad, noted that Honda, a Japanese-owned auto manufacturer, is investing in American jobs as domestic companies like Ford and General Motors have laid off tens of thousands since 2000.

“But,” he said on balance, “I would still make the argument that globalization and trade policy have been harmful for Ohio.”

Trade is good?

Ohioans prioritize jobs or income inequality over trade in polling done for the Your Vote Ohio project. And Americans, on the whole, view free trade as good, though better for businesses than workers.

Pew Research has found that two-thirds of the public said trade is good, but only one in five said it creates jobs or increases wages.

Anti-trade sentiment, Pew found , was most prominent among Trump fans. In the heat of the primary, 67 percent of Trump supporters viewed free trade as bad for the U.S. — only 43 percent supporting other Republican candidates said the same.

In an open-ended question asked during and after the presidential primary, the UA poll measured more than 1,000 Ohioans’ top problems and preferred solutions.

Men, Baby Boomers, full-time employees and residents of the manufacturing heavy northern portion of Ohio were more likely to pick trade. Women, younger generations, the college-educated, central and southeast Ohioans prioritized jobs and, even more so, issues of poverty and inequality.

Only 27 of the 1,089 respondents singled out trade as a top problem; 27 more offered trade-related solutions, ranging from penalizing employers who off-shore jobs to rewarding companies that hire American workers. Many Ohioans cited too few American jobs and too many foreign imports. Others advocated for stronger enforcement of active trade deals with 20 of the world’s nearly 200 countries.

But when each of the 1,089 respondents was asked to pick between jobs, poverty/inequality or trade, only 118 picked trade. But the issue, with the potential to interest disenfranchised union workers and social conservatives alike, transcends political ideology.

“Trade is an issue that cuts across party lines,” said John Green, director of the Bliss Institute at UA. “So it can attract all kinds of voters. This kind of cross-cutting issue can be every effective mobilizing voters otherwise inclined toward the other party.”

Pew Research, a nonpartisan think tank, found that among presidential primary voters two thirds of Trump-backers and less than half all other Republicans viewed free trade as bad.

Trump appears to be capitalizing on growing resentment for free trade among Republicans. The Chicago Council of Global Affairs, which supports globalization, has tracked public opinion on the subject since 1998. In its online panel of 2,061 American adults earlier this year, the institute found a similar gap in support for free trade between Trump’s core supporters and other Republicans. The ongoing poll also found that Democrats over the past eight years have become more supportive of globalization while Republicans, once the champions of free trade, have soured on the subject.

Manufactured resentment

Ohio trails only California and Texas in manufacturing employment or output.

Core goods — autos, machinery, engines, iron, steel and rubber products — account for more than half of Ohio’s exports and barely a third of the nation’s.

This makes manufacturing king in Ohio, and Ohio more susceptible to forces like global competition and trade, which disrupt manufacturing.

Anti-trade sentiment is strongest among Ohioans most adversely impacted by globalization: Middle-aged men with no more than a high school education and who work and live, or once did, in manufacturing-heavy communities.

Among the 54 Ohioans mostly deeply concerned about trade, 24 live in northeast Ohio, home to the former steel and rubber capitals of the world.

Concern over free trade was less pronounced in central and southeast Ohio. With proportionally fewer employed in manufacturing there, that makes sense, said Ryan Augsburger, vice president and managing director of Public Policy Services at the Ohio Manufacturers’ Association, a lobbying and advocacy group for the industry.

Automotive is still “pretty big” and spread throughout the state, Augsburger said. But there is a sense, even if the facts do not bear it out, that opposition to trade is stronger in communities where industry was not ready to absorb workers displaced by foreign imports and cheap overseas labor.

“We get that sense,” Augsburger said, countering that automation and technological advances have cut deeper than free trade.

“The reality is there is more product coming out of manufacturing in Ohio than ever before,” Augsburger said. “Yeah, there’s less jobs, but that’s party because of efficiency; we’re making more products and higher quality products with fewer man hours.”

Frustration

Most survey respondents, in their apparent frustration, asked that jobs return.

“America needs to stop buying things from outside the country,” said a respondent, a high-school educated moderate who added that “made in America” is good for jobs and taxes.

Respondents were guaranteed anonymity regarding their comments to allow for more open conversation.

“Return manufacturing jobs to the states,” said a moderate Democrat from northeast Ohio, a region particularly sensitive to trade. “Stop exporting manufacturing jobs,” echoed a conservative Republican from the state’s southwestern region.

“Sending our jobs overseas,” a moderate Baby Boomer from northwest Ohio told pollsters is his biggest problem.

Why? “They did it to my job.” His solution? “Put a higher tax on companies that send things back.”

“Stop letting China make everything and bring factories back to the states,” said an independent voter from southeast Ohio.