As colleges around northeast Ohio moved to remote learning earlier than planned this fall, Kent State stayed the course with its original plan to remain in-person until Thanksgiving break.

Limited testing made it difficult to know the exact scope of COVID at Kent, but recent maps created from state zip code data indicate the severity of the campus outbreak was on par or even less than some other areas of the region.

One reason may be the concerted efforts of Kent’s custodial team, which launched efforts early in the pandemic to try to contain the coronavirus.

Associate Director Todd Burdette unlocks the door to a room full of boxes and equipment that University Facilities Management has acquired in the battle against the coronavirus.

"This is like a thing from ET, remember the movie?" he says as he shows me a hood that looks similar to a helmet an astronaut might wear. There’s a hose that connects to a battery-powered filter belted at the waist.

"It's the HEPA filter which filters out you know 99.7 of all contaminants specifically designed for COVID-19," Burdette said.

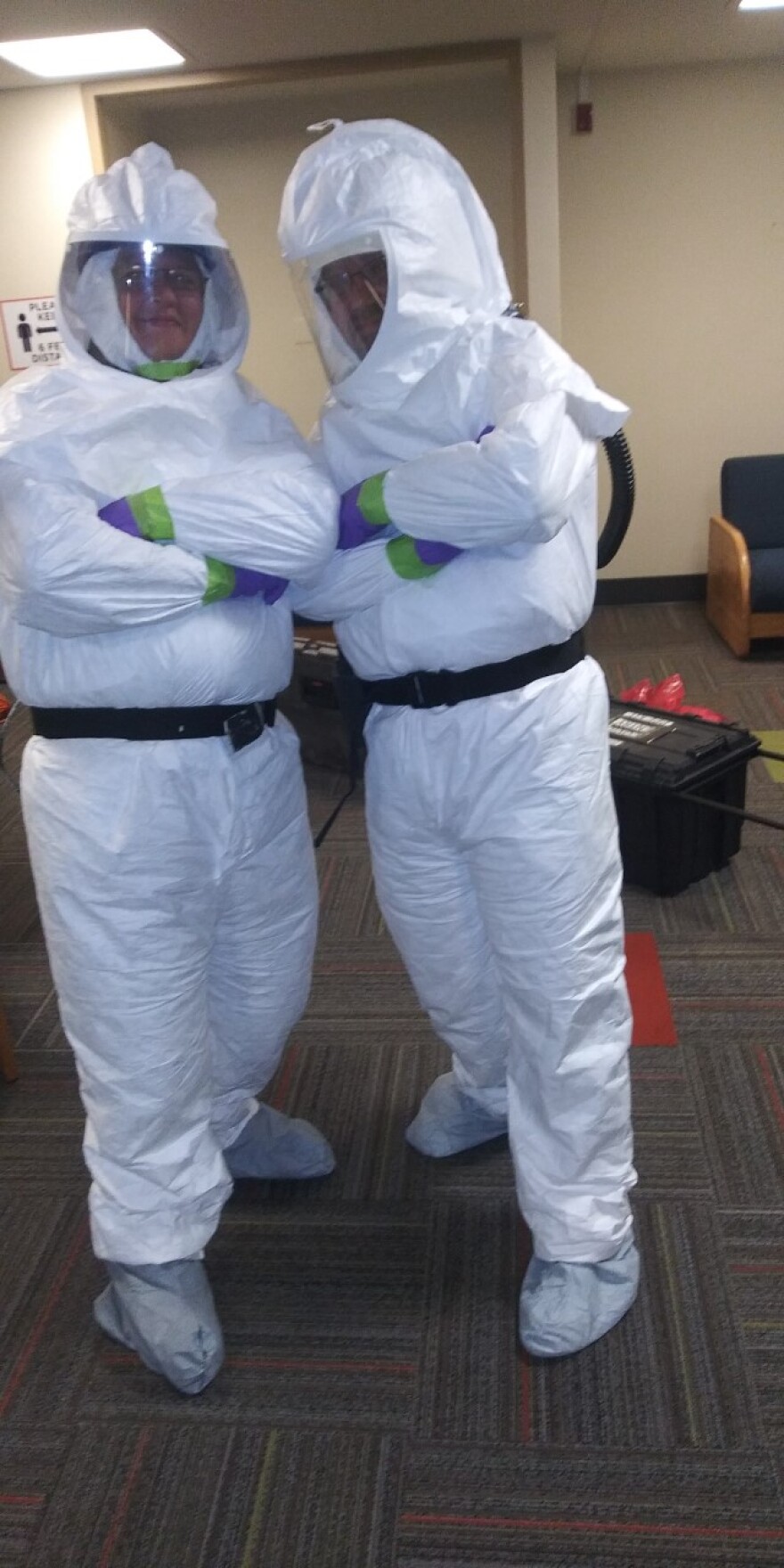

Called a PAPR—or Powered Air Purifying Respirator—this is the top of the line protection for custodial workers like Don Grubb, a crew leader who cleans residence halls.

"I kind of feel like a marshmallow man almost," Grubb said.

Along with the PAPR, he wears an impermeable Tyvek suit when he goes into areas of quarantine or isolation.

"It took some while getting used to, but now it's like second nature," he said. "And you feel protected in it? Yeah," he said.

That protection includes a full complement of attire. "You got the boots. Put on your nitrile gloves. Put on your hood. Strap on your battery pack and blower and you are about as safe as they can be," Burdette said.

Not only safe, but relatively economical. Burdette says the seven PAPR kits they have didn’t cost much because his staff made most of them early in the pandemic.

"A little bit of it's ingenuity, a little bit of it's desperation because at the time, as I said, you know, the N95 masks were hard to come by. The face shields were hard to come by. Even the Tyvek suits have been very difficult to find," Burdette said.

So Burdette says UFM employee Sean Bruce got creative with equipment they’ve used in hazardous materials research areas "... to go into those air handling type units or exhaust type unit," Burdette said. "And it was just, it was a perfect transition into what we're doing right now.”

Cleaning strategically

That involves disinfecting wherever it’s needed. They regularly hit high-touch points around campus and when it comes to cleaning COVID-exposed areas, Burdette breaks it down into three levels from least urgent to quick response.

"We developed the protocol for active, COVID disinfecting and that is the full PAPR suit you can go in immediately. We use two types of disinfectants."

One comes from a machine that’s been in almost constant use. It's a Clorox 360 fogger. The university managed to get four of them, even though in some cases they had to wait three months or more for delivery. They also have battery-powered electrostatic sprayers--10 backpacks and 30 handheld units--that work similarly.

"Let's say this box was contaminated all the way around, you could hit it and it would create a fog that would come this way. And since it's electrostatically charged, it would actually circle, encompass, and stick and disinfect," Burdette said. "Two minutes, the COVID-19 is gone. It's dead."

For areas with a less urgent need, Burdette says they close the door for 48 hours then enter and clean with normal personal protective equipment. The third option is to close the space for a week.

"If you shut the door for seven days, COVID-19 is dead OK," Burdette said. "It won't survive on the surface. It's definitely not airborne and we go in and then we just do a general disinfecting."

But a recent New York Times article questions the value of all this surface disinfecting in the battle against a virus researchers have found is transmitted through airborne particles. It suggests ventilation and filtration are more important.

The university’s environmental health and safety manager, Dennis Baden, referred questions to spokesman Eric Mansfield who said in an email the university has deployed new filters in some places and is expanding the use of an air-cleaning technology called needlepoint bipolar ionization, which emits charged molecules that can remove pathogens from the air. Mansfield says these are now in all rooms where students have isolated and they’re in the process of installing them in athletics and dining facilities.

Staying the course

When asked if he had any doubt the university would be able to remain open as planned through Thanksgiving, interim Housekeeping Manager Darrell DeLoach said "in October." He oversees cleaning in residence halls and recalls a time a few weeks ago when things looked grim.

"We had up to 8 floors on quarantine and we were down 11 housekeepers that were quarantined with those floors. So it made a tremendous strain on the people that were here," DeLoach said. "It was a big challenge, but oh my goodness. We all stepped up and we've come through this pretty well."

DeLoach says they’ve tried to accommodate the needs of students who are getting nothing like a normal college experience. Sophomore Jaiden Morales from Lorain lives in Centennial Hall where he has his own bathroom, sharing it with just one other person.

“But they are not cleaning our bathrooms. They sent out an email because of COVID they’re not entering like a private residence. Now for Eastway and public ones that like 40 people go into they clean no matter what.”

Morales also said crews are removing trash, which has piled up exponentially because dining has been mostly to-go.

Crews have also had to deal with cases of COVID-19 among the staff. But Burdette, who became associate director just two months before the pandemic struck, is confident "Not one maintenance person has contracted COVID-19 or developed symptoms due to the job they're performing."

He says those who’ve been sick have all been able to return to work. Neither Don nor Darrell has had COVID-19. Both hope to keep it that way.

"We've kind of hit a little soft spot here in in November, and we're kind of going out, you know, like a lamb," said DeLoach.

They’re hoping to keep the lion at bay when the new year begins.