Editors's note: This is the third report in a week-long series WKSU is doing on the integration of Bhutanese-Nepali refugees, who began their migration to Akron a decade ago. This story also is part of a collaboration with the Huffington Post.

One skill many Bhutanese refugees brought from the camps in Nepal is weaving. In Akron, the skill has taken a new twist. In a week-long collaboration with the Huffington Post on the impact of refugees on Akron, WKSU’s M.L. Schultze visits with the women who are “Woven in Exile.”

It’s a Sunday afternoon and the women sitting on the floor of Mongali Rai’s small apartment on Akron’s north side are debating colors and patterns.

“We’ve got this diamond pattern. Should the triangle outline be teal or blue or green?”

They’re working on the themes for the spring collection, looking ahead at the soft greens and geometric shapes that may appeal to an international market.

Mongali Rai, Mon Maya Rai and Ash Maya Subba are a core team today in a group that started in 2010 with a small nonprofit called “Woven in Exile.” They began with purses to sell at craft fairs and farmer’s markets. These days, the market for their work, while small, is international. That’s because of the other two women in the room.

“I can’t market. She can market, I can sow.”

That’s Liz Kuhn who has a master’s degree in weaving. The “she” she’s referring to is Amy Kratzer, founder of the nonprofit Girl Set Free. More on her in a moment.

'The biggest miracle that would happen is ... the weaving.'

But first to Liz and her husband, Terry Kuhn, who are also referred to as grandma and grandpa by some of the kids in the Nepali community and as honorary Bhutanese by the Bhutanese Community Association of Akron. They started Woven in Exile shortly after they became aware that a group of refugees were arriving in Akron from camps in Nepal. In the camps, the charity Oxfam had distributed back-strap looms.

Ash Maya Subba demonstrates at a maker fair. Simply put, they’re looms that hook around your back and to a tree, with the weaving going on in between.

Subba is now 64 now, with six grown children. She has a broad smile and a low chuckle and is talkative in Nepali, but – as with many older people in the community -- she relies on kids like Bersha Ghimirey to translate.

“The biggest miracle that would happen is when she started doing the weaving,” Bersha explains.

Subba is not talking about in Nepal. She’s talking about a miracle in Akron. And it’s not financial. It’s emotional – a way out of isolation.

“She was on the verge of depression every day. She didn’t have anything to do. She was sick all the time. … Every night she used to cry.”

Liz Kuhn says the group has been an outlet for even those who don’t weave.

“One of the interesting things about this when we started working with them, we would set a place, somebody’s apartment. And especially the older women, some of them would just be sitting there, just wanting to be a part of it. Not weaving. Just wanting to be there with everybody.”

Still, with many of the refugees working hard-labor day jobs like hotel maintenance, Kuhn says weaving – even small projects like purses -- can get set aside. But not with these core three. This year, they graduated to creating more complicated weekender bags.

“We feel like as our market falls in love with these products and their stories, it will grow,” explains Amy Kratzer. The nonprofit she and her husband started sells clothing and other items created by what Kratzer describes as vulnerable women, including women trafficked around the globe.

Last year, she discovered the Kuhns and their group.

'These women are not going to weave the rest of their lives. But there are other women in the community who can learn and, I believe already know how to do this.'

And in their first big venture, they created the Nilam weekender bags – the first to incorporate leather stitched to the woven cloth. Kratzer describes as a metaphor for the two cultures coming together.

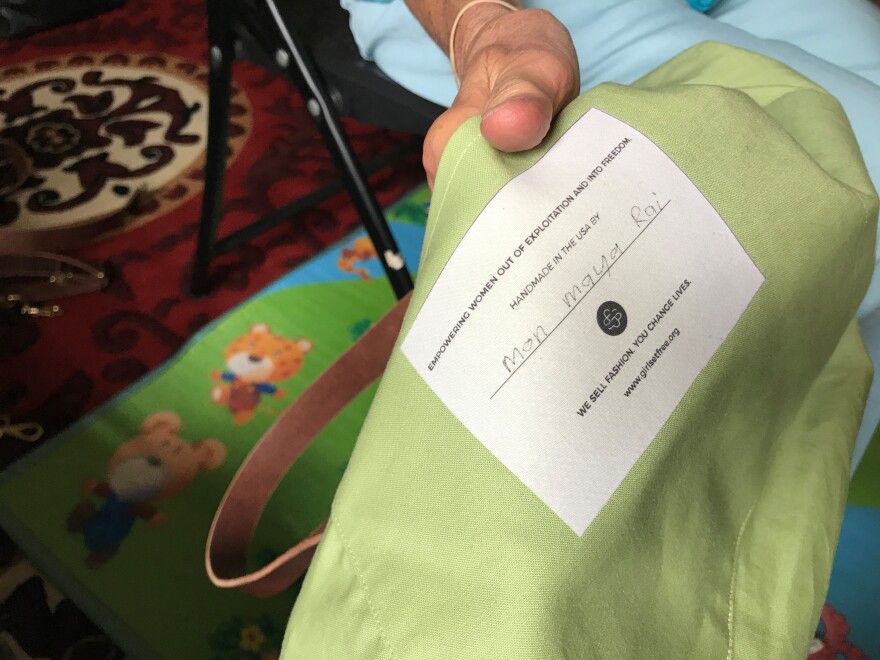

All 21 bags – at $269 each -- sold out within 24 hours. Mongali and Mon Maya Rai and Ash Maya Subba got $100 from each bag they created.

Kratzer says the goal is far bigger.

“I see them as leaders and directors eventually over this, the weaving program. These women are not going to weave the rest of their lives. But there are other women in the community who can learn and, I believe already know how to do this.”

Through Bersha, the three women say the extra money is important but so is the need to be active and appreciated.

“Because they make so many bags, they don’t know. But when people compliment, they’re like this one’s good, this one’s beautiful, this one’s really nice. They don’t know because they’re modest. They don’t like to think what they do is good than before because they try hard on every bag.”

And as they sew their names into each bag they made, Liz Kuhn says they’re gaining confidence in their work and in themselves.

COMING TOMORROW: We examine one of the ways Akron is fight its broader infant-mortality problem and takcing the language barrier at the same time.

Here's how a backstrap loom works:

AN EXPLAINER: Is it Bhutanese or Nepali?

Many of the refugees identify themselves as Bhutanese, many as Nepali, many as both, and increasingly, many as Bhutanese-Nepali-Americans.

Here's why: About 270 miles of northern India separates Nepal and Bhutan. For more than a century, Nepali-speaking people known as Lhotshampas had settled in southern Bhutan, though they maintained their own language and culture. When the Bhutanese government began a “One Nation, One People” policy in the 1980s, that led to jailing, loss of citizenship and property and the eventual expulsion of as many as 100,000 Lhotshampas. For the next two decades, they lived in what grew to be seven refugee camps in southeast Nepal. Amnesty International called it “one of the most protracted and neglected refugee crises in the world.”

In late 2006, President George W. Bush announced that the United States would resettle as many as 60,000 of the refugees here, and that number is now closer to 85,000.

AN EXPLAINER: What’s a refugee?

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, refugees are people who:

- Are located outside the United States;

- Are of special humanitarian concern to the United States;

- Demonstrate that they were persecuted or fear persecution due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group

- Are not firmly resettled in another country;

- Are admissible to the United States

For the legal definition of refugee, see section 101(a)(42) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

Click here for a link to the screening process for refugees applying to come to the United States.

Click here for the update on refugees posted by the U.S. State Department the day President Trump was inaugurated.

President Donald Trump announced last week he is capping the number of refugees allowed in the United States over the fiscal year that began Sunday at 45,000. Refugee resettlement agencies like the International Institute of Akron had been hoping for at least 75,000. President Obama had OK'd 110,000.