Editors's note: This is the first report in a week-long series WKSU is doing on the integration of Bhutanese-Nepali refugees, who began their migration to Akron a decade ago. Tomorrow, we’ll explore the fusion of music that is emerging. This story also is part of a collaboration with the Huffington Post, which is bringing its "Listen to America Tour" to Akron today.

This month, Akron and Summit County are expected to introduce a plan outlining the practical things it takes to be a welcoming community for refugees. That contrasts sharply with a move last week by President Donald Trump to cut the number of refugees allowed in the United States by two thirds. WKSU’s M.L. Schultze is taking a closer look at the progress of the largest group of refugees now settled in Northeast Ohio.

Akron is celebrating just about every outward sign of the resettlement of Bhutanese refugees – from the Nepali grocery stores to the recovering housing market to the festivals that transform urban parks into a swirl of color and sound.

Tiffany Ann Stacy – who consults with area businesses on cross-cultural issues – puts it this way:

“The majority group is no longer primarily concerned with surviving and now they’re moving onto living normal lives.”

But perhaps the strongest sign of that is, in fact, survival. Just a few years ago, suicide was a major concern. Nationally, the rate among Bhutanese refugees was twice the general population – and higher than among other refugees. A study by the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services found nearly 9 percent of the Bhutanese refugees here had PTSD. About a third had anxiety, nearly as many suffered from depression. Locally, a dozen people in the refugee community had died by suicide over four years and there were lots of stories of others who tried.

'This is our home and there are people who care about us.'

But last year, that dropped to just two deaths among Asian-Americans in all of Summit County.

What is working?

Dr. Surendra Bir Adhikari, a medical sociologist with the Ohio Department of Mental Health, says the change required awareness in the mental health community and a decision in the refugee community to take control of the problem. He says it begins with acknowledging problems:

“We know you are having a hard time. But this is your country now.”

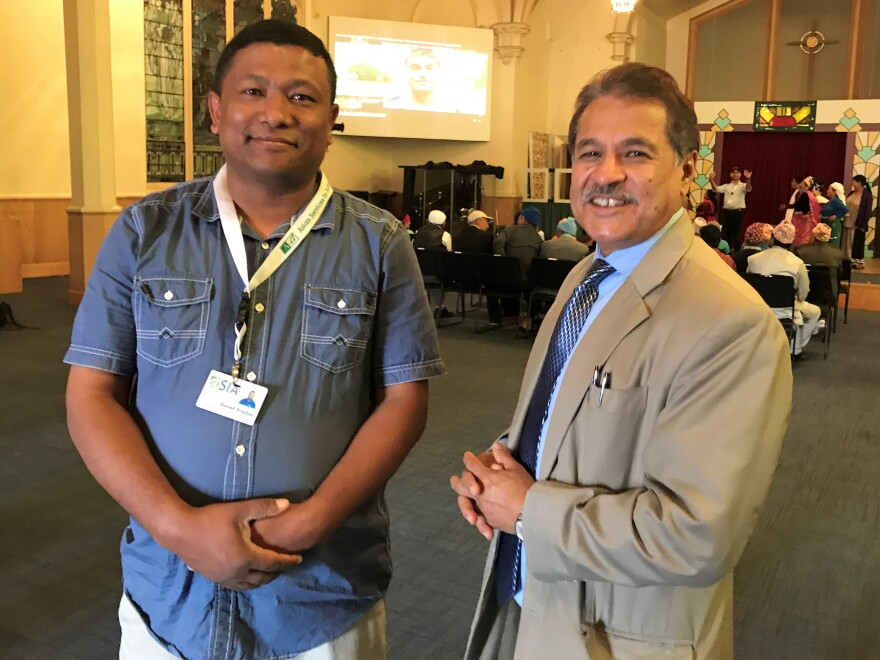

Amber Subba was, until recently, a case manager at the International Institute of Akron and has helped settle about 3,000 of his country men, women and children in the area. He’s also a composer, writer and passion behind the “Stop Suicide” effort adopted by the Bhutanese community here. Subba was among the first to arrive in 2008 – and acknowledges Akron wasn’t ready. Language was a barrier, jobs were iffy.

“Nobody had a car, nobody had driver’s license and we didn’t have proper training about how to use the bus. And we didn’t know about snow and things like that.”

Now, he says, just about everybody has relatives already here. There’s a community association, Kirat, Hindu and other religious groups, and language and citizenship classes. And, Subba says, there’s a welcoming Akron.

President Donald Trump announced last week he is capping the number of refugees allowed in the United States over the fiscal year that began Sunday at 45,000. Refugee resettlement agencies like the International Institute of Akron had been hoping for at least 75,000. President Obama had OK'd 110,000.

“There are so many such people who are coming to the community and made us comfortable, whoa, this is our home and there are people who care about us.”

Still, he says, trauma comes with losing family, property and homeland -- and with spending decades on-hold in camps that were supposed to be temporary.

“Because of the stigma, they don’t really want to share their problems. They don’t want to be like a weak person.”

Different tools for different cultures

So combating the isolation takes more than traditional counseling.

ASIA Inc. hosts groups called Lucky Seniors for older and disabled Nepali refugees in an old stone church on Akron’s east side. There’s dance, chatter, a shared meal. And there’s a version of musical chairs -- without the chairs and with a lot more serious purpose.

About a dozen men and women gather in a circle. They pass a ball, and when the music stops, the holder must share something. Most choose song. It’s safe and culturally beloved. But some talk about anxiety.

Dr. Adhikari, who came to observe, gives a rough translation of one who sounds almost as if he’s longing for camp life.

“‘When we were in the camp, we were all together, but now, here, we are all separated.’”

Ganesh Pradhan works with ASIA Inc. He spent 19 years in the camps, as a teacher, counselor, and kind of small-town mayor. He says the biggest challenge remains language, and it deeply affects a patriarchal society.

“Every single step belongs to interpreter. People miss their tongue. … good talented seniors, they become dependent to the children.”

Dr. Adhikari says that’s because the children have learned English.

“Here you have the elder generation (who) are trying to navigate their new life here. Then you have the younger generation who are acculturating pretty fast to the new life here. So there’s a gap here.”

Hope for the future

But the younger generation is also the reason many came and are gaining confidence in the U.S.

Twenty-two-year-old Nilam Ghimirey plans to be a doctor. But on this late summer afternoon, she serves as interpreter for her grandfather, Chandra, and a group of other Bhutanese elders.

They acknowledge language remains a frustration.

“They feel very bad that when they get out of the house and see their neighbors, all they can do is wave. They feel like they want to talk to them but can’s say anything. They feel like even dogs here can understand English.”

But her grandfather adds that any problems are worth it.

“He’s happy that the kids and grandkids are doing well, and he will be even happier when grandkids are able to further their education and do something better in their lives.”

And the group laughs as he looks at her expectantly.

Tomorrow, WKSU will listen to the music the refugees have brought to Akron, and the move toward a fusion with Western music to produce a new "Akron Sound."

AN EXPLAINER: Is it Bhutanese or Nepali?

Many of the refugees identify themselves as Bhutanese, many as Nepali, many as both, and increasingly, many as Bhutanese-Nepali-Americans.

Here's why: About 270 miles of northern India separates Nepal and Bhutan. For more than a century, Nepali-speaking people known as Lhotshampas had settled in southern Bhutan, though they maintained their own language and culture. When the Bhutanese government began a “One Nation, One People” policy in the 1980s, that led to jailing, loss of citizenship and property and the eventual expulsion of as many as 100,000 Lhotshampas. For the next two decades, they lived in what grew to be seven refugee camps in southeast Nepal. Amnesty International called it “one of the most protracted and neglected refugee crises in the world.”

In late 2006, President George W. Bush announced that the United States would resettle as many as 60,000 of the refugees here, and that number is now closer to 85,000.

AN EXPLAINER: What’s a refugee?

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, refugees are people who:

- Are located outside the United States;

- Are of special humanitarian concern to the United States;

- Demonstrate that they were persecuted or fear persecution due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group

- Are not firmly resettled in another country;

- Are admissible to the United States

For the legal definition of refugee, see section 101(a)(42) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

Click here for a link to the screening process for refugees applying to come to the United States.

Click here for the update on refugees posted by the U.S. State Department the day President Trump was inaugurated.

President Donald Trump announced last week he is capping the number of refugees allowed in the United States over the fiscal year that began Sunday at 45,000. Refugee resettlement agencies like the International Institute of Akron had been hoping for at least 75,000. President Obama had OK'd 110,000.