The International Institute of Akron had expected to resettle hundreds of Syrian refugees in Summit County this year, though President Donald Trump’s indefinite ban on Syrians disrupted those plans at least temporarily. WKSU’s M.L. Schultze visited with one of the roughly 10 Syrian families who have migrated to Akron in the last six months.

Johaina and Radwan al Nassar set out a large platter piled with basmati rice, peas and chicken. Around it are splashes of brilliant purple and deep greens: soup, salads, tabouli, grape leaves, envelopes of dough stuffed with homemade cheese -- even Syrian pizza. All laid out on a tablecloth stretched across the living room floor.

“The guests in our culture, three days. Yeah, you have to come three days,” Radwan explains.

This two-story frame house in North Akron has been home for the couple and their three small children since they arrived from Jordan in October. She doesn’t speak English yet, though she’s taken a few classes at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. He arrived equipped with three years of training in what he calls “British English” and a gregarious nature. So he speaks for them both.

He also has a bachelor’s degree in computer science and hoped to stay ahead of the growing tensions in Syria – maybe even start his own business.

“But the war was faster than me.”

The Arab spring's collapse

'Death is the end. Maybe after one day, two days, a month. You can't live there.'

The couple married seven years ago, shortly before the Arab spring emerged -- and collapsed into a bloody civil war. They’re from Jasim, a southern Syrian town that had about 31,000 people – before the protests, the air strikes, the barrel bombs, the executions. The now-29-year-old Radwan says he had grown up with cautions about what to say and to whom and taps on the wall.

“People say, ‘You know the walls have ears. Walls have ears.’”

But that was just the way of life was in Syria. Now, he says, there is no life there.

“The death is the end. Maybe after one day, two days, a month. You can’t live there.”

The camps

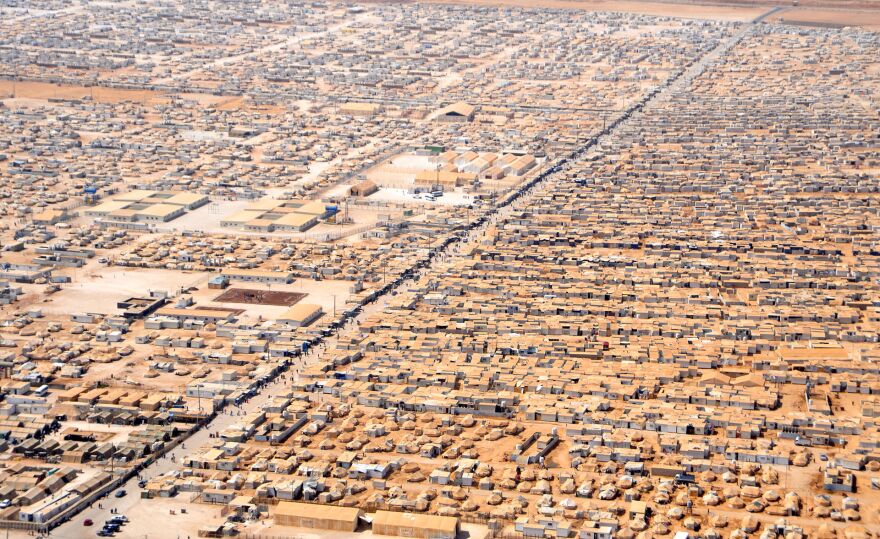

So by March of 2013, the Nassars headed to Jordan along with their then-two children, his mother and father and some of his nine brothers and sisters. They joined close to 100,000 other refugees in the al Za’Atri refugee camp -- 2 square miles, he says, of dust and dirt and desperation.

Before long, Radwan came up with a house outside the camp the extended family could rent – but only by breaking one of the biggest rules in Jordan: Refugees cannot work.

He was arrested for working and would have automatically been deported back to Syria. But there was a conflict along the border, so instead he was sent to a second camp -- away from his family for two months.

“I can’t forget that two months. That’s the hardest two months of my life. If you want to get bread, you have to walk in the desert about 3 miles. If you want to get water, cold water, you have to walk four miles.”

He took advice from those who understood the system and wrote a letter to the prime minister. He was released to rejoin his family. And he began making plans to return to Syria.

'I told her I want to travel to my children's future. She said, Good.'

An unexpected turn

Then refugee services asked if he wanted to travel elsewhere. Where? he asked. The U.S., they answered.

Radwan pauses and looks at his now three children: Khaled --- who wants to be a pilot. Next to him, Asmaa, who will need surgery for a club foot. And the always-smiling Anfal – born a refugee and happily unaware of it.

Radwan says all he saw was his children when he talked to the refugee screener.

“I told her I want to travel to my children’s future. She said, ‘Good.’” As if on cue, Anfal climbs onto his lap.

Vetting

The decision was one thing. The vetting another. An examination of all the documents they brought from Syria. Fingerprints, retinal scans, six- and seven-hour interviews done in separate rooms by different screeners. Radwan says the screeners already knew the answers to the questions they asked and were looking for any discrepancies. There were none and clearance came in October: The Nassar family would be heading to Akron, Ohio. He knew nothing about Akron, but started educating himself.

“What is that Akron, where is that? Where is Ohio? When I start reading about that, I know there is a lot of snow here.” And that was fine, he said. “I like cold.”

Instead, he got a really warm Ohio fall. But that was fine, too.

“Everything was so amazing. I like the tree, the water, the ducks.”

The family arrived at the Akron-Canton Airport with their identities sealed in a plastic bag marked with the initials IOM – the International Organization for Migration. Like most refugees, they also had an loan -- in their case, about $4,100 to pay for things like transportation, housing and food. Radwan got a job in a tool-and-die shop and they began repaying the loan in about two months.

Meanwhile, the International Institute of Akron was doing for the Nassars what it’s done for a hundred years, helping the family find get their employment, education and cultural feet in the U.S. and find a home.

Radwan says the housing is very different from Syria.

“But in our customs, we care about the neighbors first, not the house.” And they like their Akron neighbors.

National politics

Radwan says he understands a nation’s desire for safety, but is unclear why President Trump has drawn the lines he has on refugees. He says there are many others, like himself, who want to come to the U.S. to realize what he calls their “humanity.”

“No one asks you about: Where are you from? What’s your language? What’s your religion? What do you believe in? No. You are human. That’s it.”

Radwan is still talking about starting his own business, perhaps as furniture maker. Or, he looks over at his wife, maybe opening a Syrian restaurant in Akron -- with her as the chef.