This year marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Celebrations were planned around the world, nearly all of them scuttled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

But a local Beethoven scholar has quietly kept working at home.

By listening in on 200-year-old conversations, Kent State University musicologist Ted Albrecht has shed new light one of the biggest mysteries surrounding the composer.

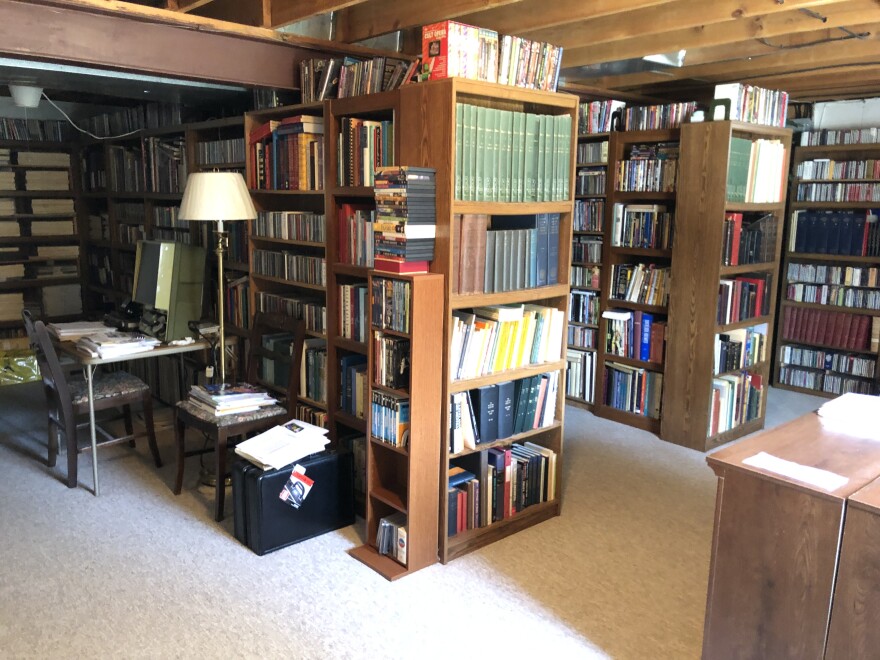

Albrecht’s home office is filled floor to ceiling with books, documents, and letters by and about Beethoven. His basement serves as a fully-stocked Beethoven library.

A musician and conductor, Albrecht is also a world authority on the legendary 19th century composer.

He reaches onto a shelf to share the raw material for his latest project. It’s a facsimile of one of Beethoven’s conversation books.

The size of a modern paperback, the book's unlined pages are covered with faint pencil scrawlings, snatches of long-past conversations, mostly about life's most mundane topics. They're filled with details of a doctor's visit, grocery lists, passionate arguments over politics, jokes and asides.

Albrecht last year visited Bonn, Germany, Beethoven’s hometown to to experience the sensation of holding one of the books in his hands.

“It’s what the Germans call Fingerspitzengefuhl,” he said, 'the feeling at the tips of the fingers.'

First ever English translation

Beethoven as we know, lost his hearing, and in the final decade of his life and carried blank books for people to write out their side of conversations to which he would reply aloud.

There are 139 of these books, and Albrecht is writing the first English translation in 12 volumes.

He’s been at it for more than a decade, having just finished volume eight.

He says the conversation books allow us to eavesdrop on Beethoven’s everyday life, "with all the details you don’t find otherwise.”

“It’s all very human,” Albrecht said.

One page takes us back to Sunday, September 11, 1825, around noon.

A small group has gathered to hear one of Beethoven’s latest string quartets, No. 15 in A minor, Op. 132.

Albrecht describes the scene, “They were in a private dining room in one of the big hotels in Vienna,” a frequent haunt of the maestro.

A young woman, a future baroness, is presented to Beethoven. He signs her autograph book, “and then somebody else here writes, ‘Oh, she really likes to play your stuff.’”

Beethoven is in high spirits, having recently recovered from a long illness.

An Englishman in the audience holds a written conversation with the maestro. He later tells a friend that, “Beethoven can still hear a little if you 'Hallo' quite loudly into his left ear.”

It’s one of dozens of clues Albrecht has discovered that debunk the myth that Beethoven was entirely deaf to the world around him.

He had a little hearing left, despite the legendary episode at the premier of his ninth symphony.

Beethoven's ninth surprise

It’s Friday, May 7th, 1824.

Beethoven is on stage with the orchestra, his back to the audience.

He’s not conducting, the maestro's hearing was far too poor for that, but he's following the score as part of the performance.

The oft repeated myth is that at the end of the symphony, Beethoven, deaf to thundering applause, had to be turned around to see the adoring crowd. It's a sad and poignant picture of life's ironic cruelty.

Albrecht doesn’t quite buy it.

“It doesn’t make sense now that we know he could hear a little bit,” he said.

Albrecht believes it likely happened earlier in the performance.

“In the second movement," he said, " during the timpani interjections.”

“The audience went crazy,” said Albrecht.

But Beethoven had his eyes on the score.

“He didn't perceive that the white noise that was behind him was applause,” explained Albrecht.

Here is when the alto soloist turned Beethoven around to see the audience clapping, which was unusual in the middle of a movement.

Beethoven bowed slightly to the crowd and returned to the music.

It’s a version Albrecht says was confirmed by entries a week later in one of Beethoven's books.

No time for bad taste

The conversation books also reveal much about Beethoven the man, even though we only see half the conversation.

Albrecht points to times when Beethoven’s response is implied.

For example, “when the local newspaper editor tells him an anti-Semitic story, Beethoven goes only so far with it, and he cuts off the conversation,” Albrecht said.

In another instance, his favorite violinist, a little drunk, conveys an off-color story about Mozart and a female pianist.

“Within a couple pages," Albrecht says, "Beethoven cut the conversation off.”

Beethoven apparently had bigger things on his mind.

We have the image of the scowling, angry Beethoven, but that’s not the character who emerges from the conversation books.

“There were some really deep feelings there,” said Albrecht, about the man he's spent decades getting to know.