Updated September 4, 2022 at 7:30 AM ET

NASHVILLE — Marie met her husband, Shaun Varsos when they both worked at a movie theater in Nashville in 2006 or so. A few years later, that movie theater flooded and was turned into a shooting range where the two would go shoot guns together.

That anecdote took on a tragic irony when Marie's brother, Alex Youn, got a phone call the morning of April 12, 2021.

"Shaun had shot Marie and my mother," he says.

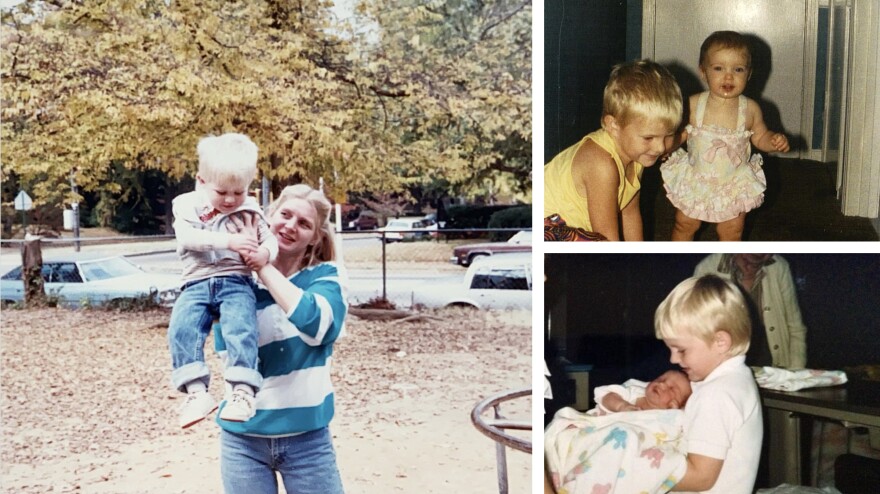

Alex lost his mother, Debbie Sisco, 60, and his younger sister, Marie Varsos, 31, the people to whom he was closest - in an instant.

In the month leading up to their tragic deaths, records left by Marie show that she had exhausted every option available to victims of domestic violence to try and prevent what she saw coming.

But the system was not enough to protect her.

Marie had left a trail of the domestic violence that led to her death at the hands of her husband

Alex remembers being overcome with grief. It was like being trapped in some horribly tragic movie.

"It just hasn't seemed real and it still doesn't seem real," Alex, 37, says. "It's been hard to sort of process it."

He flew from San Francisco where he lives now back home to Nashville. To try and cope, he kept himself busy. He had so much to get done - planning their funerals, and settling their estates.

It was during this process that Alex found something that spurred him to turn that grief into action.

He remembers opening his sister Marie's laptop. It was locked. But then there, by the track pad, was a sticky note. With her computer password on it.

"It was almost like a sign that she wanted me to have access to her computer," Alex says.

And on that computer, Marie had been documenting her husband Shaun Varsos' abuse and her efforts to escape it.

She left notes to herself. She had texts from Shaun. She even made audio recordings of some of their fights, and Shaun's threats.

"It sort of really sort of weirdly turned into a solving a murder mystery," Alex says.

Marie had left a trail.

And her brother decided he was going to follow it, retracing the steps Marie took to get protection from law enforcement, and the courts.

"And through that process, I discovered the irregularities, the loopholes and the failures in the system," Alex says.

Failures that he believes led to the deaths of his sister, and their mother, Debbie Sisco.

Her family called the police to report the abuse but dispatchers said there was no one to help at the moment

Marie's attempts to get help from law enforcement and the courts began on March 7, 2021. Marie and Shaun had a horrible argument.

In recordings found on Marie's computer, she shouts, "Stop! Don't put your hands on me!" Shaun then wrapped his hands around her neck, choking her until she passes out.

When she came to, he was holding a gun to her head. She told police that he threatened to kill her, her family and himself.

Experts say strangulation and threats with a gun are two of the biggest warning signs that a domestic violence case could become lethal. And the police should have responded urgently.

But they didn't.

Marie escaped from Shaun. An hour later, she and her family sat in a pickup truck outside an empty police station, trying to file a police report. Bruises were forming on Marie's neck. Her mom, Debbie, was in the backseat, comforting her.

But when they called the police, they were told by dispatchers that they would have to wait.

"They're working on getting out there to you. There's just nobody in the precinct right now," the dispatcher says. "So what's going to happen is a patrol car is going to have to free up from whatever they're doing and come to. But they do have to take those life threatening emergencies first."

Alex, Marie, and their mom, Debbie, were in disbelief. Didn't her case qualify as life-threatening?

Alex kept calling. For hours. His frustration grew and grew.

"My sister was choked out when she passed out and her husband threatened to shoot her ... my patience is gone"

"I'm trying to be as appreciative and waiting as long as possible," Alex says to dispatchers. "But my sister was choked out when she passed out and her husband threatened to shoot her and threatened to shoot himself. So my patience is gone."

"That timeframe was completely unacceptable for response time to a victim," Metro Nashville Police Capt. Kevin Lovell later told Alex. Since Marie's death, Lovell says domestic violence calls are categorized differently to get victims help quicker.

Eventually, Marie was able to file a police report that night and get a temporary order of protection from the court. Shaun was charged with assault and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

He was summoned by the sheriff's office the very next day to pick up the order. But he walked in and out of the office without being arrested. The sheriff's department says when they ran Shaun's name, they didn't see any warrants ... even though one had been issued the night before.

It wasn't until days later, when Marie notified law enforcement of Shaun's location, that he was actually taken into custody.

"That has definitely been an issue that has come up many times; is the separateness of the work that the sheriff's department does and the work of the Metro police," says Susan Tucker-Smith, with the Office of the District Attorney Nashville-Davidson County.

The sheriff's department says it has added one more step to its process to notify the police in cases like Shaun's.

And then another mistake: Shaun was accidentally released early.

And another: Marie was never notified - even though she signed up for the state's victim notification system. A sheriff's deputy failed to follow through and would later be disciplined for it.

Records show Marie even tried to fix the department's mistake.

"I never got a notification, or a missed call, or anything that that happened so I just want to make sure my contact info was correct," she says in a call to the city's non-emergency line later that week.

And then there were the guns - the court ordered Shaun to give them up.

But Tennessee has no method to enforce that ruling. Part of the problem is that someone who has been ordered to turn in their guns can give them to a licensed firearms dealer, law enforcement or — the most potentially dangerous option — a third party like a friend or a relative.

"We're saying we trust you to give this gun to someone, and not to steal it back or have access to it whenever you want or for that third party to just give it back to them," says Becky Bullard of Nashville's Office of Family Safety, which works with domestic violence victims.

In Shaun's case, he said he was going to give his guns to his dad, but there is no documentation of that ever happening.

On April 12 of last year, Shaun took his guns, zip ties, and battery acid to Marie's mom's house. He waited outside in a rental car.

Marie and Debbie spotted him and tried to run away. But he shot them on their neighbors lawn.

Then he shot and killed himself.

In Nashville, nearly half of suspects in domestic violence homicides were prohibited from having access to a gun.

Tennessee has one of the highest rates of women killed by men, ranking 10th in the United States. Experts say guns play a big role in that statistic; in domestic violence situations, the risk of death is five times greater when a gun is present.

"We are not waiting for a homicide to happen," says Bullard of Nashville's Office of Family Safety. "They have happened and they are happening — they continue to happen — with individuals who should never have a weapon."

Domestic violence victims face similar barriers because when abusers are determined it's hard to stop them

These barriers that Marie faced are not unique to Nashville.

It's a challenge for domestic violence victims all over the country, says Ruth Glenn of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

"If they fall through the cracks or their needs aren't being addressed or something really bad happens," Glenn says. "It's mostly because they're a domestic violence victim, and our systems are not set up as properly as they could be to address the unique needs of every domestic violence victim."

To protect victims, Glenn says there needs to be a coordinated response. But they interact with so many separate agencies that don't work together it creates a safety net with too many holes in it.

And as Marie's case illustrates, that's a problem — especially because domestic violence abusers are incredibly determined, Glenn says.

"When they decide that something bad is going to happen, it's almost impossible to stop them," Glenn says. "They will cut off a GPS. They will go put a false record to get a gun. They will sit in the dark for two hours. The list goes on and on."

Pushing through legislation to protect domestic violence victims is challenging

Glenn says pushing through legislation to protect domestic violence victims is not easy. Federally, it took three years of negotiations for Congress to finally reauthorize the violence against women act.

And here in Tennessee, Alex took everything he learned about his sister's case and brought it to the state Capitol last session.

"I wanted to make sure ..."Alex said to a room full of representatives, his voice catching. "I wanted to make sure that no one — no family — had to endure what we had to go through."

In the end, Alex helped write four bills. But because of concerns about expenses, or implementation, only one became a law. It requires more communication between sheriff's offices and the police.

But Alex says it's not enough.

"For them, they view it as one thing that went wrong with their agency," Alex says, "but coupled together there are like eight things that went wrong for this person that is dealing with the government to try and get the help they needed."

Alex says he will return to Tennessee's state capitol as many times as it takes to close the gaps that Marie fell through. For him, the fight for justice has only just begun.

Copyright 2022 WPLN News