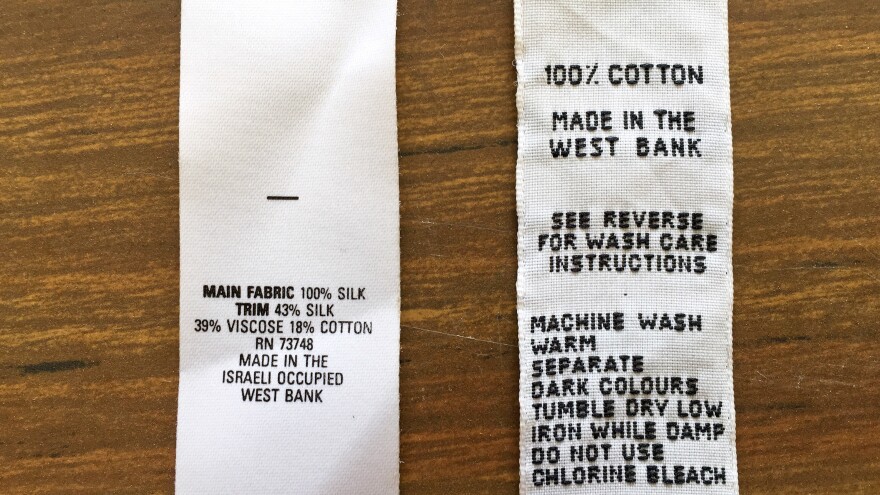

In recent years the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been playing out on a battleground that's barely a couple square inches in size. It's the labels of consumer goods produced in areas under Israeli occupation.

Last year the European Union, for example, instructed member countries to not allow imports of products from Jewish settlements in the West Bank to be labeled as, "Made in Israel." The European Union, like the U.S. considers the settlements illegal.

Instead, certain products have to be specifically marked as coming from settlements in the West Bank. This infuriated Israel. Members of the U.S. Congress denounced the move and considered legislation to counter it.

In its fine print, labeling touches some of the most sensitive issues of the conflict. It's about who has sovereignty over land. And to understand where the labeling issue started we turn back 30 years, to an experimental Palestinian lingerie factory launched in the 1980s.

Then, as now, Israeli farmers and factories operating from settlements in the West Bank export much more than Palestinian businesses in the territory.

But Charles Shamas, a Yale graduate from a Lebanese American family, went to the West Bank to try to help develop the Palestinian economy. This was before there was even a Palestinian government.

He wanted to figure out how to create good manufacturing jobs independent from Israeli markets or ownership.

"We were going to try something nobody had done," says Shamas, now 67 and living in Jerusalem.

"You had to produce a product that by its quality commanded a premium," he recalls. "So we said, well, obviously you have to be niche oriented. And (if) you're going to hit high value-added niches, you have to be able to export."

Former U.S. diplomat R. Nicholas Burns, now a professor at Harvard, knew Shamas then and describes the standard practice.

"The reality in the 1980s and 1990s was that (Palestinian) products were bought up by Israeli middlemen and shipped out of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as Israeli products with an Israeli label on them," he said.

Shamas wanted to change that. To make his case to Western policy makers, he argued a logical extension of the laws in their own countries. He said that since the U.S. and Europe do not recognize the West Bank as being part of Israel, his lingerie from there should be distinguished from Israeli products.

"Do what your understanding of your own law requires you to do," Shamas says he told Western trade officials.

He says U.S. officials found a regulation allowing the goods to be marked, "Made in the Israeli Occupied West Bank."

It might not seem like a victory these days. It didn't call the lingerie even, "Palestinian" let alone something as bold as, "Made in Palestine."

But for Palestinians involved, it was better than being identified as Israeli. And the label was seen as the lingerie took off. A collection was featured in the 1987 winter collection of Bonwit Teller, then a top New York store. It was advertised in fashion magazines.

The factory is closed now – it shut in 1990 amid bouts of West Bank violence and troubles with the Israeli military's regulations. But racks of robes and camisoles still hang in the old production room, on the third floor of a concrete building with a heavy metal door.

"It gave me pride that this item of such quality is making it to top markets in America with the label," said the former production manager, Salwa Duiabis, as he gave a tour of the old facility.

Burns calls Shamas a "pioneer" who brought attention to a "hidden issue."

Fast forward to today and that labeling is a thorn in Israel's side.

Exports from Israeli settlements make up only about 1 percent of total Israeli exports, estimates Ohad Cohen, head of Israel's Foreign Trade Commission. And they dwarf Palestinian products in volume.

But the distinction Shamas helped forge on those lingerie labels still applies.

For example, in 1995, a year after the Palestinian Authority came into existence, the U.S. changed its policy and forbade the word "Israel" from appearing on products from the West Bank or Gaza, including the phrase "Israeli occupied." They can say "West Bank" or "Gaza" now, though enforcement is often lax.

Last year's EU ruling requiring special labels for Israeli settlements in the West Bank was a watershed. European officials said they were just informing consumers about product origins, but you can hear Shamas' old logic in their reasoning – that diplomatic policies apply in trade.

"What we want to achieve with this is simply to ensure that we are abiding by the legal standards that we have put down ourselves," says the EU's ambassador to Israel, Lars Faaborg-Anderson.

Those rules are just starting to take hold but have already caused problems for Israeli settler and farmer David Elhayani. He said all the attention makes it harder to get his dates and herbs into European shops.

Six or seven years ago, he says, 80 percent of his date crop went to Europe.

"Most of our products are now going to Russia," he said.

Prices are lower. "It affects us," he added. "And when I mean us, it's the families, the children, the growers."

Critics of the EU decision say it is actually being inconsistent by requiring special labels only for Israeli settlements, not other territories considered occupied around the world.

International law expert Eugene Kontorovich of Northwestern University and Israel's Kohelet Policy Forum, who has written extensively on the subject, says Europe is using the technical issue of product labeling to pressure Israel politically.

"The reason the Europeans are doing this and not doing overt political measures is because overt political measures would require a consensus of the EU that they don't have," he said.

Critics also point out that Palestinians working for Israeli farms and factories in the West Bank are affected. One prominent recent example was a controversy over the location of the factory for the Sodastream drinks maker.

And even though the overall economic impact is still small and technically just deals with how a product is marked, Israel says the implications are part of a effort to bring economic pressure on the country.

"The labeling is just one part of the big plan," says Cohen, of Israel's Foreign Trade Commission.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxMzY2MjQ0MDEyMzcyMDQ5MzBhZWU5NA001))