Could travelers one day climb into pods and zip through vacuum tubes between Cleveland and Chicago at hundreds of miles an hour?

Regional transportation planners will study whether a Hyperloop is feasible here, though the technology hasn’t been fully developed.

It’s not the first time Cleveland has explored an ambitious transportation project. Hyperloop is up against a long history of transit dreams that never came true.

Cleveland Subway

In the early 1950s, Cleveland was at the height of its population with more than 900,000 residents.

But the city was starting to change. Cars were undercutting mass transit, according to Cleveland State University professor Mark Souther.

“There was a concern that you needed to serve the whole city, and you needed to keep downtown strong,” Souther said, “and let people access it more easily, and not just have everyone coming down into the city in their cars and clogging the roads.”

In 1953, Cuyahoga County voters broke two-to-one in favor of a downtown subway.

County engineer Albert S. Porter resisted the campaign. He advocated for highways—not trains—to relieve Cleveland’s congestion.

“The freeway system and the Inner Belt will move and distribute traffic in a much more satisfactory manner and will take out of the downtown area many vehicles which do not belong there, thus leaving the streets freer for those that do,” the Plain Dealer quotes Porter as saying the summer before the vote.

According to Souther, Porter believed that cities were headed for decentralization.

“He believed that downtown was inevitably going to lose out to the suburbs, and that you really shouldn’t try to stop that,” Souther said.

County commissioners rejected the subway in 1957. When backers tried to change commissioners’ minds in 1959, Souther said, there was a new urgency.

“Stores were starting to close,” he said. “There was a sense that downtown, if it did not have a radical change, was really slipping into decline.”

The commissioners turned down the subway a second time.

The Lake Erie International Jetport

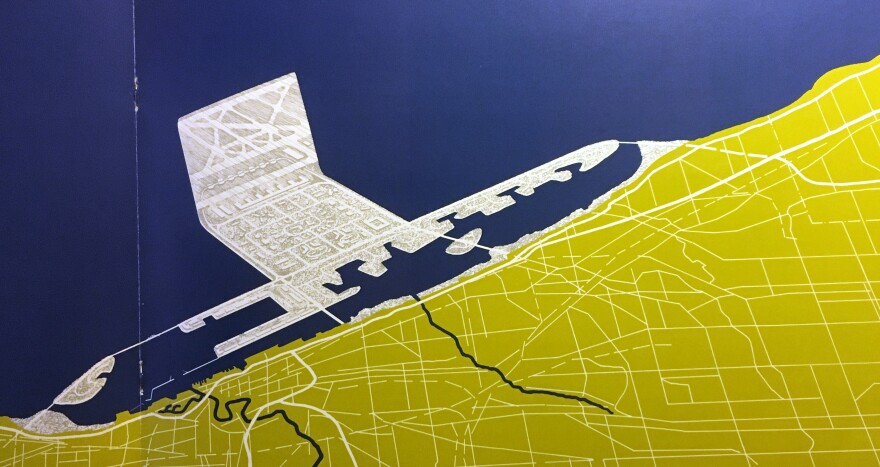

Around a decade later, a very different downtown project captivated Cleveland’s leaders: a new airport built on the waters of Lake Erie.

Abe Silverstein, the director of NASA Lewis Research Center, proposed the idea in the 1960s. It caught on with the local corporate community.

In December 1971, Gov. John Gilligan pitched a jetport alongside such business leaders as Francis A. Coy, the head of May Company.

“The Lake Erie International Jetport project holds the promise of Cleveland-Northeastern Ohio region, and the state of Ohio, once again becoming a thriving center of transportation,” Coy said. “The project provides a basis for a totally planned transportation system, around which a city and an entire region can be rebuilt.”

University of Dayton professor Janet Bednarek said air travel was growing across the country.

“A lot of places were scrambling, trying to come up with plans that would allow them to expand their airport or build a new, bigger airport that could accommodate all of the new travel,” she said.

The Greater Cleveland Growth Association envisioned jets landing on and taking off from an airport five miles offshore. The project would share space on a manmade island with an industrial park and shipping harbor. The association said it would create up to 70,000 jobs.

“There was going to be a causeway that would link to it that would carry all kinds of traffic back and forth,” Bednarek said. “It was huge. It was just massive.”

A later plan proposed building an island four-and-a-half times the size of Cleveland Hopkins, encircled by a 13-mile dike, about 4.4 miles from the Cleveland breakwater. But after more than $4 million spent on feasibility studies throughout the 1970s, the jetport never left the tarmac.

“I don’t think they ever needed it, and I don’t think that it ever was going to do what they said it was going to do, particularly before deregulation,” Bednarek said.

Downtown People Mover

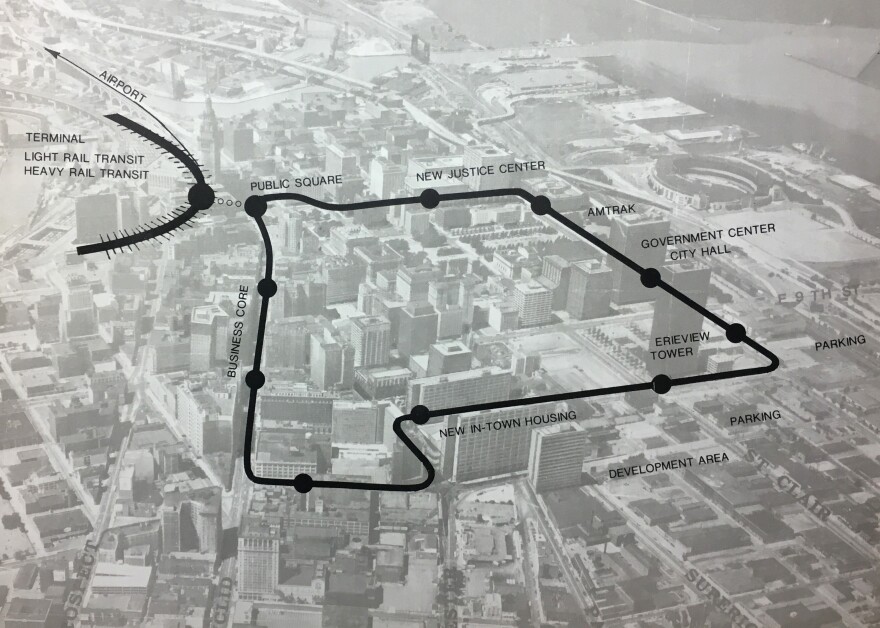

Back on land, Mayor Ralph Perk pushed a new transit idea: an elevated tram called the people mover circling downtown. In 1976, Cleveland won $41 million from the federal government to build it. Three other cities also received grants.

At the time, Perk told reporters that a federal official thought Cleveland had the finest proposal.

“He made many trips to Cleveland,” Perk said at the time. “He’s tremendously impressed with the progress being made in Cleveland.”

The city offered to chip in $500,000 for an engineering study. One of Perk’s fellow Republicans, then-Cuyahoga County Commissioner George Voinovich, opposed the idea.

“Not one dime should be spent on this project,” Voinovich said in 1977. “With a half a million dollars, we could repair the parks, we could do something about the roads and we could clean up the dirty city that we have.”

Cleveland’s planning director at the time, Norman Krumholz, criticized the people mover. In his 1990 book, Making Equity Planning Work, he wrote that he supplied Voinovich and other opponents with research and analysis.

Looking back in a recent interview, Krumholz said the Regional Transit Authority would have been stuck with the bill for upkeep.

“And ultimately, the cost of the people (mover) would have been ruinous to RTA,” Krumholz said. “And it’s the last thing in the world RTA needs, either then or now, in terms of providing basic service to the people of Cleveland.”

The next mayor, Dennis Kucinich, put an end to the project.

“Which surprised the feds incredibly,” Krumholz said. “They had never been in a situation where a mayor has sent money back to Washington.”

Ferry Route To Canada

For decades, local leaders and businesses have tried to restart a regular ferry service between Cleveland and Canada.

In 1993, port officials explored a possible route to Port Stanley, Ontario, with no success. The idea resurfaced in 1996, when a Canadian company told the Plain Dealer a ferry would be up and running by the fall of that year. By November, the plan was off again.

The Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority commissioned ferry feasibility studies in 1999 and 2003, and even selected a Dutch company to run the service, according to the Plain Dealer.

But in 2009, the Plain Dealer reported that the port’s downtown plans no longer included a ferry terminal.

Last year, Congress allowed the Ohio Department of Transportation to repurpose $8.6 million in federal money that had been set aside for the ferry project. The funds largely went to fix up the port, according to Cleveland.com.

Not every transportation plan ends that way. Euclid Avenue now hosts the bus rapid transit Health Line, built after decades of proposals for the street.

If Hyperloop does someday send people rocketing to and from Chicago, it will have avoided the fate of many Northeast Ohio ideas that fell short of reality.

Unless otherwise cited, historic quotes come from John Carroll University’ s Northeast Ohio Broadcast Archives.

![An artist's depiction of the downtown people mover as it appeared in a 1976 study produced for the city by Richard L. Bowen and Associates and Dalton-Dalton-Little-Newport. [Cleveland Public Library]](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/4ec15b8/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2792x1482+0+0/resize/880x467!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Flegacy%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F3%2F05%2F1976peoplemover_cpl.jpg)