Ernest “Mooney” Warther was an esteemed son of Dover, Ohio, and a master wood carver. The work of this turn-of-the-century artist is the foundation for the Tuscarawas County museum in his name.

The Ernest Warther Museum and Gardens includes an array of Warther creations, from his wooden steam engines to his celebrated plier tree to his steel mill miniatures to his wife Frieda’s Button House.

The museum is celebrating a new historical marker on June 8 in honor of being added to the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places.

'Mooney'

Warther was a showman according to his granddaughter, Carol Warther Moreland, the museum CEO.

“He knew no strangers, and he had a big, booming voice. He talked to anybody about anything, and you could hear him a mile away,” Moreland said.

His personality helped sell his art according to his great-granddaughter, and museum director, Kristen Moreland Harmon.

“[Dover’s] a small town. He had to advocate for his own art,” Harmon said.

Born in 1885 to Swiss immigrants, Warther got his nickname at a young age. His father died when he was 3 years old, and Ernest began working at age 5 as a cow herder.

“In Swiss, ‘Mooney’ means ‘bull of the herd.’ And as he collected the cows, everyone joked because he was the little leader of all the cows, taking them to pasture each day,” Harmon said. “That just ended up sticking with him for the rest of his life.”

Signature pliers

Warther picked up whittling at an early age to pass the time while watching the cows. When he was a boy, a chance meeting led him to discover his signature creation.

“He meets a stranger who cuts him a pair of pliers out of a single block of wood, hands them over, but doesn’t tell him how he did it,” Harmon said. “While he took those cows to pasture, he figured it out.”

He could create a pair in seconds. During his lifetime, Harmon estimates Warther created three quarters of a million pliers, charging people a nickel apiece, which would help fund his future museum.

Warther took the pliers a step further by creating a sculpture of pliers, and his first major work in 1913 was “The Plier Tree.”

Steel mill miniatures

The first room of the museum features a miniature steel factory, carved from Warther’s memories of working at Dover’s American Sheet and Tin Plate Company.

“He worked there for 24 years,” said his granddaughter, Moreland. “It’s a scale replica, and all the little parts move and operate so you can see how the men worked the steel.”

History of the steam engine

Warther grew up near a rail line and as a child became fascinated by the steam engine trains that ran past his home.

“He was able to go down and look at the engines and started memorizing them,” said his great-granddaughter, Harmon.

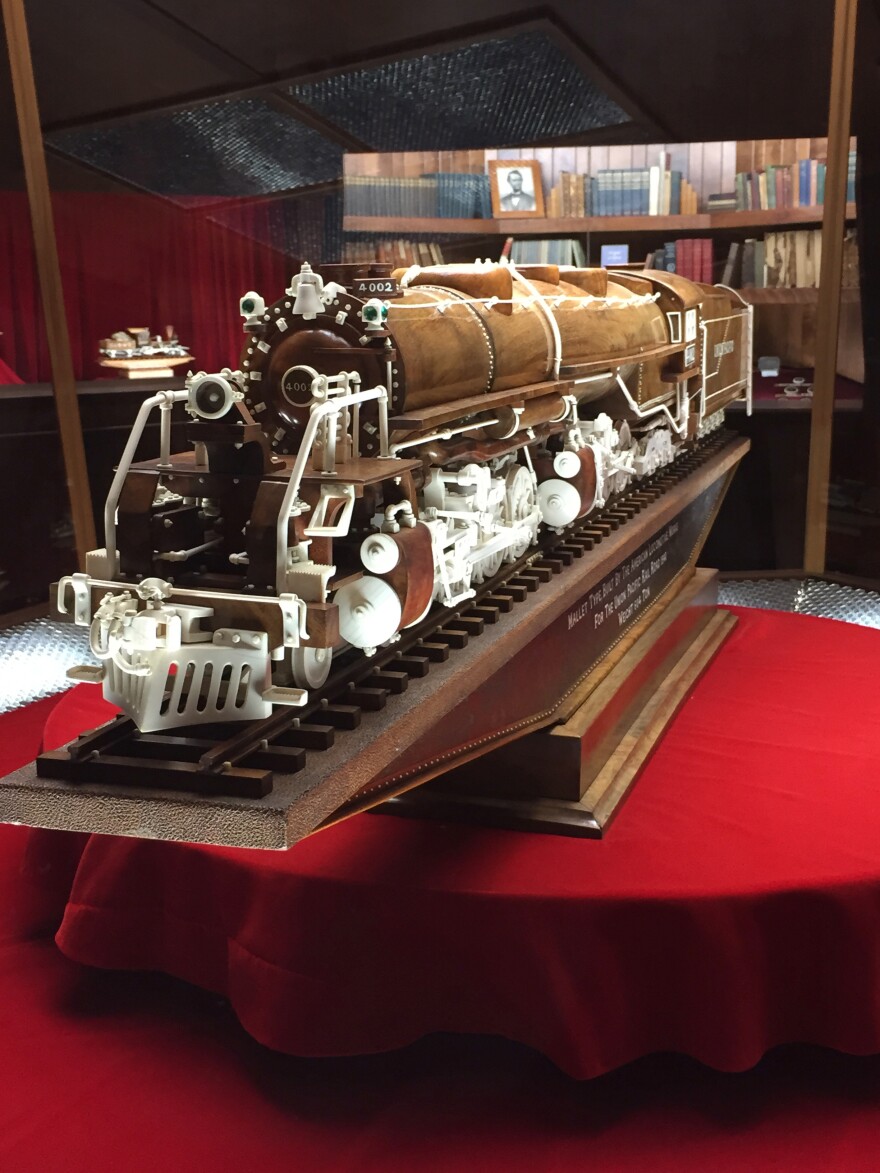

Warther soon began carving wooden replicas of the trains which led to his wood-carved chronicle of the steam engine from 250 B.C. to 1942.

The trains are mechanized and run off electric motors with leather sewing belts. Each part of the trains was hand carved by Warther and is pressed fit together, rather than glued.

Warther’s history of the steam engine took 40 years for him to carve and consists of about 35 works averaging 6,000 pieces each.

Frieda's button house

A separate building on the museum grounds spotlights the creative designs of Warther’s wife, Frieda.

Born Frieda Richard, as a girl she’d make jewelry out of buttons and developed a reputation as a button collector.

Neighbors and friends would give Frieda more buttons and over time she collected thousands of buttons in the Warther house.

Later in life, she decided to go through the buttons and got the idea to put them in patterns, which are on view in the Button House.

A lasting legacy

Ernest Warther passed away in 1973 but his memory lives on thanks to his family and fans of his woodcarvings. People from around the globe visit the museum.

“There’s kind of like, I guess, groupies,” Harmon said. “There’s people who really get into ‘Mooney’ and the history and everything he created.”

Warther had offers to buy the carvings, but he chose to keep them in his hometown.

“He thought it was very important to have everyone come to the city of Dover to see his carvings,” Harmon said.