This article is courtesy of Inside Climate News.

Dwayne Petko kneels on the concrete floor of a semi-built house and turns the knob of a large fan mounted in the front doorway, part of the most common test in his line of work.

He is the owner and operator of Energy Matters LLC, an energy rating service, and he is doing a blower door test, which tells a homeowner, or in this case a builder, how much air is leaking through a building.

“I like helping builders build better houses,” he said.

As he works, his dog, an Australian shepherd-Cavalier King Charles spaniel mix named Jackson, is sunning himself by the back door.

Demand is about to grow for professionals like Petko who have the tools and expertise to do energy audits of existing homes. Ohio, along with just about every other state, has been awarded federal money from the Inflation Reduction Act that can be used for rebates to improve energy efficiency and help to offset the costs of efficient appliances.

But Petko isn’t cheering this new funding or even sure if he’s interested in participating, a sentiment that Inside Climate News found repeatedly when talking to energy efficiency practitioners. Their wariness stems from Ohio’s recent history of building an efficiency program and then abruptly getting rid of most of it through House Bill 6 in 2019, a bill best known for its nuclear bailout and the bribery scandal that helped to put the House speaker in prison.

If the new programs are just a matter of quickly spending some federal money and then walking away, then many of the people best equipped to help say they are not sure they want to adjust their lives and jobs to be part of it. They also say that the number of people and businesses that do this work has gone down in recent years, which affects the ability to ramp up new programs.

“I think there’s a common misperception that there’s a bunch of workers sitting on the bench that can do this work,” said Julie Tolliver, owner of Energy Fitness for Homes, which is based near Cincinnati. “But they’re not there.”

At the same time, she thinks the Ohio Department of Development, which is managing the rollout, understands the challenges and is doing its best to create a workable program.

“I feel like they get it,” she said.

A department spokesman had no timetable for when the rebates will be available for consumers, but several people who are closely following the process said they expect to have a good sense of a timetable within a month or two.

Ohio is among a majority of states that have obtained commitments for federal funding and are preparing to launch the programs, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. About a dozen states plus Washington, D.C., are a step ahead and have begun operating their programs. South Dakota is the only state that has refused to participate.

The federal money must be spent by the early 2030s, and could be gone much sooner depending on how quickly and how many people seek rebates. The Trump administration has taken actions to stop the release of money from the Inflation Reduction Act, but doing so may be more difficult for these programs, which already have commitments for funding.

What the rebates cover

Ohio has received separate commitments of about $125 million from two rebate programs, for a total of about $250 million, according to the Department of Development website.

The Home Efficiency Rebates program provides money to cover part of the cost for assessing a home’s needs and then adding insulation and other measures to reduce air leakage and energy loss. The benefits have a cap of $2,000 for households that are able to reduce their energy use by 20 percent or more, and $4,000 for households that are able to reduce their energy use by 35 percent or more.

The Home Electrification and Appliance Rebates program has money to cover part of the cost of a heat pump and highly efficient appliances. The benefits have a cap of $14,000 per household, and several other caps for specific equipment, including $8,000 for a heat pump, $4,000 for upgrading a house’s electrical panel and $1,750 for a heat pump water heater.

Once the programs are up and running in Ohio, consumers should be able to work with contractors to guide them through the process of figuring out which rebates are most appropriate and what paperwork they need to submit to get the money.

“I think there’s a common misperception that there’s a bunch of workers sitting on the bench that can do this work. But they’re not there.”Julie Tolliver, owner of Energy Fitness for Homes.

In addition to the rebates, the federal tax code has incentives that can be used to offset the tax bills of people who install energy efficient appliances.

The programs and tax breaks are a good example of the government helping to meet needs that aren’t adequately addressed by regular commerce, said Tom Bullock, executive director of Citizens Utility Board of Ohio, a consumer advocacy nonprofit.

“If you leave it to the market alone, people don't do this efficiency work,” he said. “They don't invest as much as they could or should in highly efficient appliances, in insulation, air sealing, all the traditional insulation measures.”

But he also is well aware of Ohio’s prior missteps that may contribute to doubts about the state’s ability to sustain long-term solutions.

What went wrong

Ohio’s recent history of building programs and then abandoning them makes it a unique case, said Jennifer Amann, a senior fellow at the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, a research and advocacy group.

While this new money is an opportunity to lament the missteps of the recent past, she prefers to think in terms of its ability to do good for the public and help them reduce their energy costs.

“Our hope is really that the utilities will step up and get involved and work with the state so that these are programs or approaches that can continue even after this funding has been spent,” she said.

Ohio’s energy efficiency programs grew following the passage of a 2008 state law that required electric utilities to meet targets for developing renewable energy and for helping consumers with energy conservation.

As years passed, utility companies began to ask for a repeal or reduction of the requirements. They said the energy conservation benchmarks were increasingly difficult and expensive to meet as the standards moved higher.

The Ohio General Assembly got rid of future steps in the requirements with the 2019 nuclear bailout law. The law’s main features were bailouts for nuclear and coal power plants, but it also phased out electricity utilities’ energy efficiency programs. Lawmakers rationalized the phaseout as a necessary removal of impractical mandates.

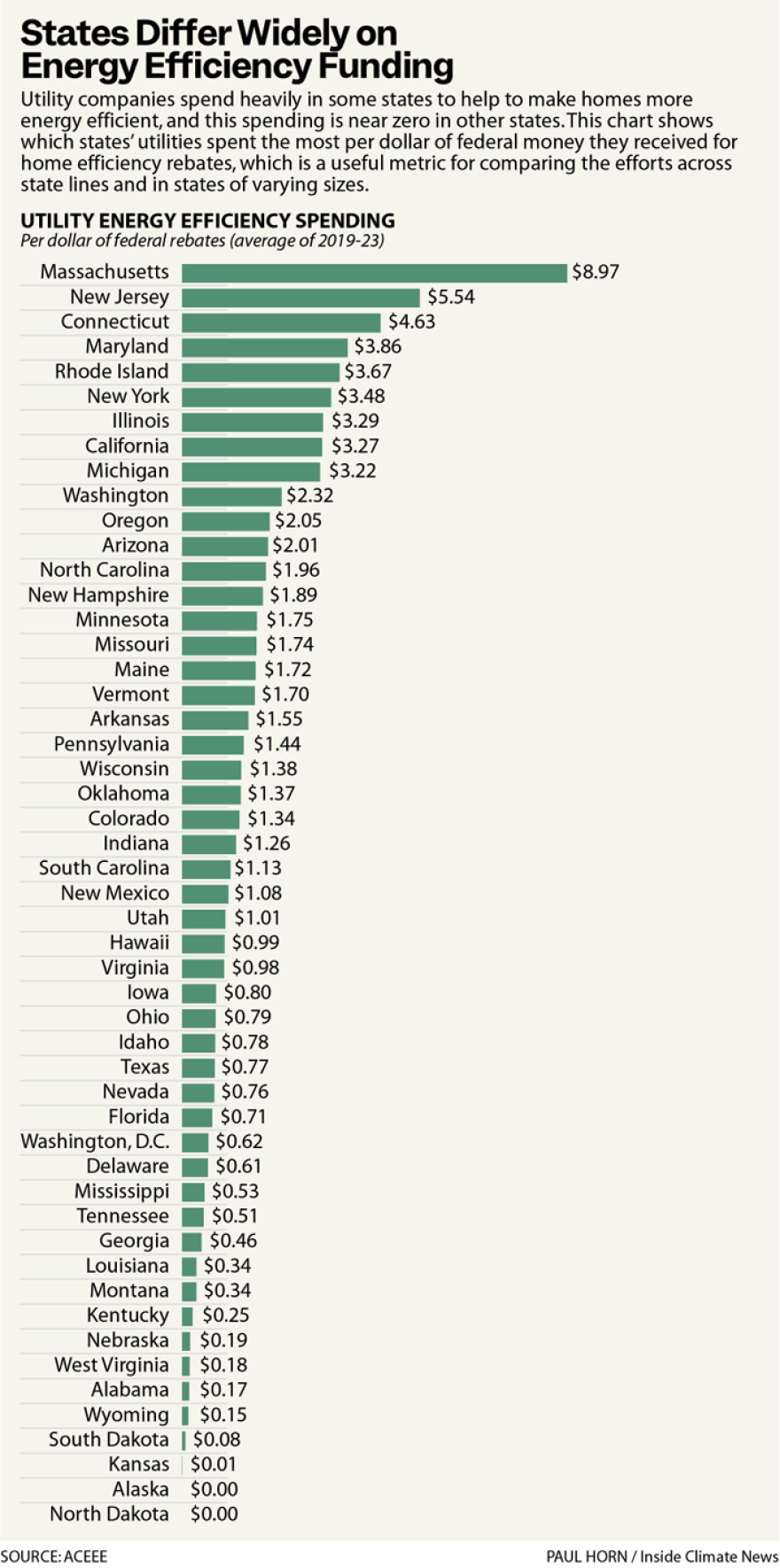

Ohio utilities went from spending $81.4 million on efficiency efforts in 2020 to $7 million in 2021 and now rank near the bottom of the country, according to ACEEE.

The loss of funding led to a sudden and painful drop in demand for the businesses that provide energy efficiency services.

Some lawmakers from both parties have attempted, without success, to restore parts of the programs.

But there is no consensus on whether it’s desirable for utilities to operate efficiency programs. The Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, the state’s consumer advocate on utility issues, has talked about how the old programs were not well-designed to maximize benefits.

“Federally funded energy programs are a good way to promote energy efficiency,” said spokesman J.P. Blackwood. “This is a better model than utility-funded programs, which turn utility-sponsored energy efficiency programs into a profit center for the utility, through mechanisms like decoupling, and lost revenues. This artificially raises the price for energy efficiency for participants and non-participants who may end up funding the program through utility rates.”

Wary of a sugar rush

Nate Adams has little good to say about Ohio’s history with energy efficiency and the hopes that the federal money can have a positive effect that endures.

He is a writer and energy efficiency consultant who now lives in West Virginia after spending most of his career in Northeast Ohio. He is known online as Nate the House Whisperer, and is one of the few people who can call themselves an energy efficiency influencer.

“The money will run out suddenly and not permanently shift the market—yet another sugar rush,” Adams said about the new funding.

“Our hope is really that the utilities will step up and get involved and work with the state so that these are programs or approaches that can continue even after this funding has been spent."Jennifer Amann, senior fellow at American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy

He has seen several iterations of federal or state funding becoming available, and has found that the programs suffer from design flaws and a lack of long-term vision.

His larger concern is that the country needs a massive campaign to make its housing stock more efficient and reduce energy waste, and to shift away from burning fossil fuels in buildings. He views these home-focused programs as way too modest in their vision to be able to address the needs.

“The business model for energy audits and effective retrofits sucks, to be frank,” he said. “There are only a few companies in the country doing it, they max at $1 million to $3 million in sales per year, and they are basically driven by the grit of one owner. Take that person out of the equation and they die.”

He is touching on a common theme for energy efficiency professionals, which is that some of their most important work is not profitable or only marginally profitable. For example, most houses need to do air sealing to fill the many spaces where hot or cold air from inside is leaking to the outside. Doing this is difficult and dirty, often involving weatherstripping, caulk and other materials.

Back at the house in Sunbury, Petko said he is undecided about whether he will seek work related to the new rebates. He has concerns similar to those of his peers Adams and Tolliver, but he would much rather discuss building science than federal or state policy.

His larger worry with government efficiency programs is the difficulty in reaching people with the most needs.

“The people who are interested in energy efficiency a lot of times already have a pretty good house, and the ones that have a poor house aren't interested in going through the measures to get someone out there to make the repairs and the upgrades,” he said.

And that’s a problem too big to be solved by a short-term program.