Jami Cozza is still getting settled.

In February, she was evacuated from her East Palestine home after a train carrying toxic chemicals derailed within a mile of her residence. Since then, she and her three-year-old daughter have bounced from hotel to hotel – until now.

Cozza has finally found a new place for them to live, in the nearby city of East Liverpool. But, she’s still scared.

“I’ve had anxiety that I haven’t felt in years,” she said.

Three months after the train derailment, fears in East Palestine linger. Many have questions about the controlled chemical burn’s impact on their physical health – and those concerns have led to a concurrent mental toll that the small village isn’t equipped to handle.

East Palestinians are trying to build enough resources to take care of their neighbors suffering from severe anxiety, but it’s an uphill battle for a municipality of its size.

Unfamiliar territory

Even as she starts planning decorations for her new home, Cozza can’t help thinking about what she left behind.

The dark clouds of the chemical burn felt like an ending to her.

“It was almost like all my childhood memories with my dad were gone. He just passed a year ago,” Cozza said. “Him taking us to the rollarena, him taking us to the park – I just felt like everything was under that cloud.”

Since the disaster, Cozza has had severe panic attacks. She’s had to supplement her anxiety medication with more counseling. There are still moments where her emotions feel out of control.

“It's all the questions that you can't even start thinking about yet,” she said. “I get a lot of questions: 'Are you ever going back? What are your plans? Where are you going?' And it’s like… I don’t know.”

That’s normal, according to Dale Panzer, a psychiatrist who has experience evaluating residents in the wake of train derailments. Although everyone responds to traumatic events in different ways, he said potential chemical exposure comes with a lot of unknowns, and our minds tend to fill in the blank with the worst-case scenario.

“Uncertainty just inevitably leads to stress and anxiety,” he said.

That stress is then exacerbated by being displaced from home. Those who are evacuated from their homes are more likely to experience anxiety, he said.

“The earlier somebody gets back to their routines and some semblance of familiar life, the quicker their level of stress and anxiety is likely to go down,” he said.

Most East Palestine residents were able to return home after two days of evacuation. But some like Cozza still don’t feel safe going back.

Finding the resources

In a survey of 500 of the village’s 4,700 residents, around 60% reported anxiety in the wake of the derailment, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

Three months later, Marcy Patton said stress levels are still high. She leads the Columbiana County Mental Health and Recovery Services Board, which has been providing crisis counseling and mental health support since the derailment.

“We're seeing symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder: people may have trouble sleeping, people may have problems with their appetite, panic attacks,” she said.

In response, her organization started a stress management class and a community support group to fill a gap in resources. The small community doesn’t have a lot of counselors.

Lindsey Rotnem is one of the few. She’s a case manager with Insight Counseling, one of the only mental health clinics in town. She said there’s still a lot of stigma about seeking mental health care within the Appalachian community.

“There's a sense of pride,” she said. “In this community, we work hard, and we don't want to ask for help, we don't want to get help from other people.”

Rotnem is from East Palestine, and she said that background helps people to trust her.

That’s why Patton’s organization is working to start a course to train community members – people who already live there – in mental health first aid.

“Anything we can get that comes from the community and people they trust, I think is better,” she said.

A long-term solution

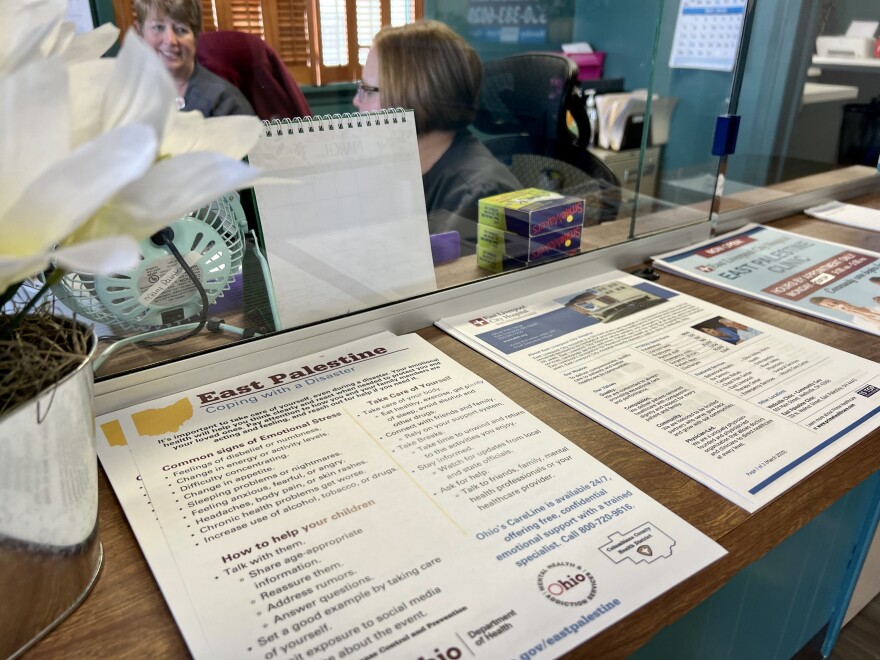

In the meantime, a new East Liverpool Hospital clinic in the village has behavioral health specialists who are open for appointments. No longer just a temporary clinic, it will stay open to help mitigate the long-term effects of the traumatic event.

Lori Colian, director of treatment services at the Columbiana County Mental Health and Recovery Services board, said she thinks the community needs to be prepared for what’s coming down the line.

“The whole PTSD, the hearing of the train sirens, being somewhere close to ground zero,” Colian said. “It's normal to have reactions after a traumatic event, and sometimes they don't happen right away.”

The clinic sits right next to the railroad tracks. As patients share their fears, they can hear the rumble of the trains passing by.

That sound used to feel like home to Cozza. It soothed her. But, the derailment has caused all that to change.

“Now, you know, every time you hear that train coming, it's like, ‘Is it going to happen again. What's going to happen?’”

She said it’s hard to focus on building a new life when those questions constantly race through her head.