The gilded age of publishing is over, and with it, it would appear, the splashy debut. Gone are the seven-figure advances and the 22-city book tours. And that's just fine. Writers were never meant to be rock stars, and publishing them as if they could be was absurd. Writers become writers because they are comfortable alone. Out of that silence emerges a kind of music that doesn't need screaming fans.

It's fitting, then, that in this season of diminished expectations, the best debuts of the year have about them a stillness and beauty that make them feel like throwbacks. The Chekhovian lilt to Daniyal Mueenuddin and Paul Yoon's debut collections; the modernist melancholy of Paul Harding's new work; and the old-world dramas of Shahriar Mandanipour and Petina Gappah all feel as if they come from another time.

Once The Shore

Once the Shore, by Paul Yoon, paperback, 224 pages, Sarabande Books, list price: $15.95

The eight stories of Yoon's debut form a kind of floating city in which water is the essential element of everyone's lives. The sea brings travelers and part-time waiters to the South Korean island where the tales unfold. Water supplies fishermen and gift-shop owners their livelihood. It even becomes the metaphor for a widower's emotional reverie. "In the heat of the remaining sun," she thinks of her late husband, "she swore you could see a curtain of mist rising from the peak of his thin head."

For Yoon's cast, resilience is not just a stance but an aesthetic. Women grow old and do not marry. Young men are lost at sea. All the while, they soldier unfussily on. Thus, in the rare moments when the men and the women in this book yearn for more, their resolve feels all the more poignant. We know, instinctively, that Yoon's lush sentences will end in heartache. (Read from Yoon's story "The Hanging Lanterns of Ido," about a young married couple who meet a stranger with an unexpected connection.)

Tinkers

Tinkers, by Paul Harding, paperback, 192 pages, Bellevue Literary Press, list price: $14.95

There are few perfect debut American novels. Walter Percy's The Moviegoer and Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird come to mind. So does Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping. To this list ought to be added Paul Harding's devastating first book, Tinkers, the story of a dying man drifting back in time to his hardscrabble New England childhood, growing up the son of his clockmaking father.

The mystery and machinery of these ticking timepieces appear and reappear throughout this beautiful book, which cycles backward and forward in time, capturing with awful grace the unwinding of a life. George Washington Crosby, the book's dying hero, awakens out of delirium into the terror of his body's revolt. His loved ones, sitting nearby, might as well be in another country: that of the living, the healthy. Harding has written a masterpiece around the truism that all of us, even surrounded by family, die alone. (Read about the hallucinations that fill George Washington Crosby's final days.)

In Other Rooms, Other Wonders

In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, by Daniyal Mueenuddin, paperback, 256 pages, W.W. Norton, list price: $13.95

Fifty years ago, Bernard Malamud won the National Book Award for his story collection The Magic Barrel. There are echoes of that book's casual mastery and patience in Mueenuddin's debut collection, which was a finalist for the same award this year. Only Mueenuddin's debut doesn't unfold in the Jewish enclaves of Brooklyn, but rather the mud-clapped floors of servant quarters in rural Pakistan. His characters, like Malamud's, are often stuck in an old order, even as the world tilts on and Pakistan's feudal society begins to crumble.

It will certainly not go gently into that good night, however. In "Nawabdin Electrician," a vain and hard-working man thwarts a robbery and watches coldly as his attacker dies, pleading for blessings. "Saleema" tells of a young housemaid who thinks she finds love in a 50-year-old toothless servant, who -- kind as he is -- ultimately tosses her aside as so many have before him. Just as the industrialists fight over Pakistan's growing spoils, the people on the bottom -- so beautifully captured here beside their employers and masters -- mirror their ruthlessness. Mueenuddin writes of this generational upheaval with the steady telescope of absolute prose control. The beauty of his sentences is deceptive. It can make us read of the cruelest things. (Read — or listen to Mueenuddin read — the complete opening story of the book, about the crafty and determined electrician Nawabdin.)

An Elegy For Easterly

An Elegy for Easterly: Stories, by Petina Gappah, hardcover, 240 pages, Faber & Faber, list price: $23

2009 featured two terrific story collections by African writers about men and women getting restless in their marriages, anxious about their careers and worried for their families. One was superstar Chimamanda Adichie's marvelous The Thing Around Your Neck; the other came from a young trade lawyer from Zimbabwe who began writing fiction just a few years ago –- Petina Gappah.

An Elegy for Easterly, Gappah's wry, corrugated-metal prose debut covers the spectrum of life in Zimbabwe today through the daily dramas of jealous wives, children hankering from a bauble from abroad, and snooty emigrants who have come home to Africa after years in the U.S. Gappah is an earthy, evocative stylist, with a startling range of storytelling styles. "Hotel California" unfolds as a tale within a tale, while "The Negotiated Settlement," one of the more moving stories within the collection, lays bare a marriage in beautiful imagery. "First you undo me this scar," says the narrator's wife, "then we can talk about divorce." A writer who can strike bone this solidly can tell us just about anything. (Read Gappah's story "The Mupandawana Dancing Champion," about a man, forced out of retirement, who builds coffins.)

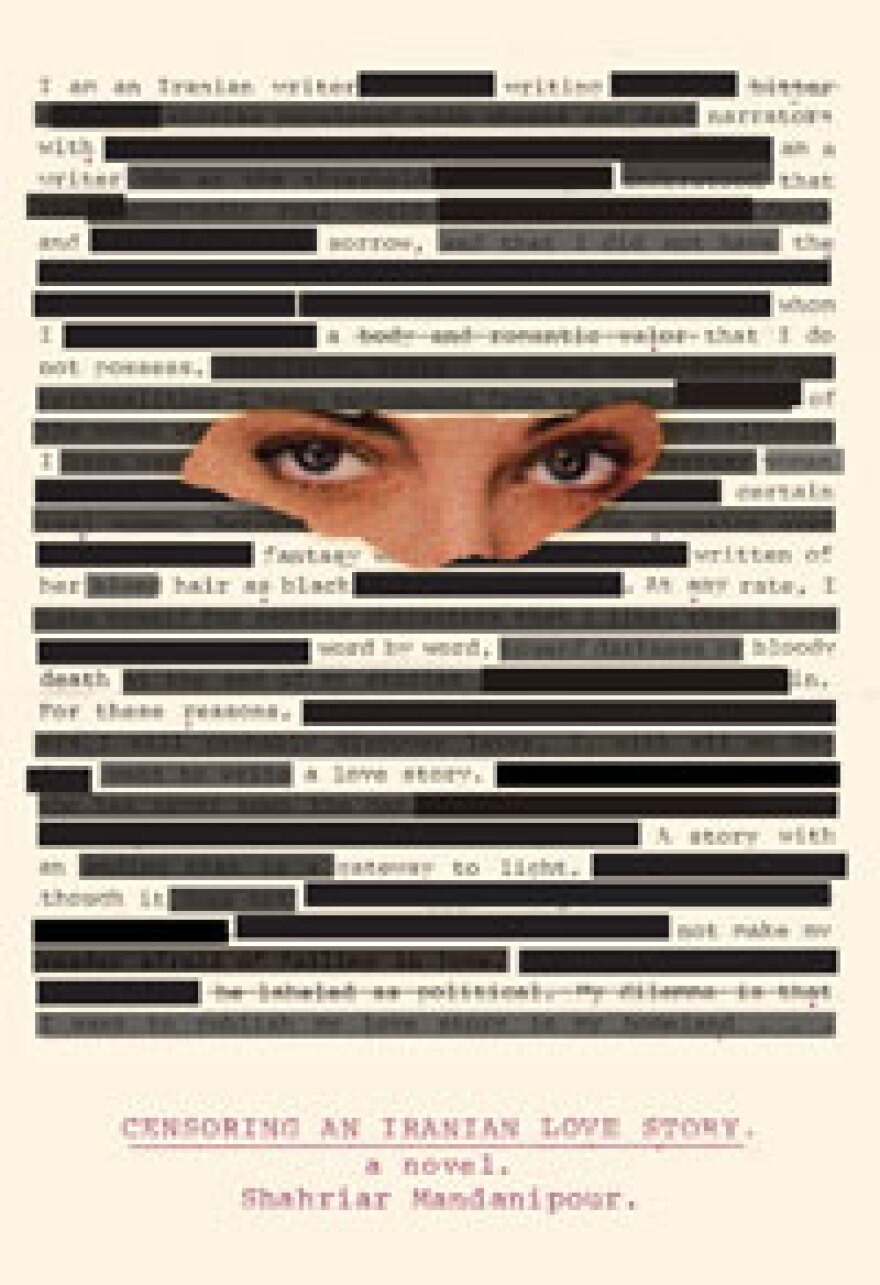

Censoring An Iranian Love Story

Censoring an Iranian Love Story, by Shahriar Mandanipour, hardcover, 295 pages, Knopf, list price: $25

Books have always been one of the great aphrodisiacs, especially in a culture where a book's meaning can be as hidden as a body beneath garments -- as in modern-day Iran. Shahriar Mandanipour's American debut -- he has published many stories in Farsi -- manages to meditate on this dilemma in contemporary Iran while also telling a poetic love story.

In Censoring an Iranian Love Story, a young man falls for and seduces a woman by posing as a bookseller so he can hand her The Blind Owl, a novel by the beloved but often censored Iranian writer Sadeq Hedayat. Scattered throughout the ratty paperback is a series of purple dots, which spell out a message in code. The lovers leapfrog from Hedayat to a library, where they trade letters in code in borrowed copies of The Little Prince, The Unbearable Lightness of Being and other books.

The narrator of this tale is a frustrated novelist named Shahriar, who realizes that much of what he writes will be censored. So parts of the evolving love story appear crossed out and in bold, a grim reminder of what counts as offensive to authorities in modern-day Iran. Readers who've tired of the enjoyable but culturally flat gamesmanship of the Jasper Fforde novels have a new frontier in this tremendous book, one that speaks volumes to the indomitable quality of love. (Read as Mandanipour's narrator describes the scene of a protest "in such a way that [he] cannot be accused of political bias.")

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.